Cries of the Missing: The Tragedy of Missing/Murdered Indigenous People– ‘None of Us Are Safe Until All of Us Are Safe’

Viewers of the award-winning movie Wind River may have had those thoughts as they sat in the comfort of cinemas nationwide in 2017. Unfortunately, as is often the case, art was imitating reality.

The movie focuses on the case of an Indigenous teenager’s rape and death after her body is found by a federal wildlife agent on Wind River Reservation in Wyoming. It shines a light on the attitude of non-tribal society’s response to that case -– and in far too many real-life cases.

“I watched the movie,” Emily Sitting Bear, of the North Dakota Three Affiliated Tribes told The Daily Muck. “I’m not qualified to give an opinion on the writing and the acting -– and I have to say what happened in the movie doesn’t happen every single time with every law enforcement agency and non-tribal community -– but sadly, that is the experience of many tribal families in many cases.

“Families have a daughter or son missing, they know something does not sit right. It is out of character for them to do this,” Sitting Bear continued. “The emergency exists, but they are not taken seriously and do not get the same level of attention and service and support that a non-Native American would receive.”

Sitting Bear is the director of the tribe’s Emergency Operation Center and co-chaired the Tribal Homeland Security Advisory Council, which released its final report on how to best address the American tragedy of missing/murdered Indigenous people (MMIP) to the Department of Homeland Security in January.

Her family tree has branches in all three affiliated tribes – Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara.

While more people and news outlets are aware of the once-invisible tragedy of missing and murdered Indigenous people, Sitting Bear said she still talks to people who are surprised and shocked by the numbers associated with this problem.

“They had no clue,” she said.

Everyone can agree the high number of unsolved murders, rapes and missing individuals is a tragedy. Most who see the statistics for this issue may consider it a travesty and a tragedy.

More comments from Sitting Bear and the THSAC are included later in this article, but now we look at the numbers that demonstrate the severity of the issue and one case that puts a face to this crisis.

A Child in the Wilderness

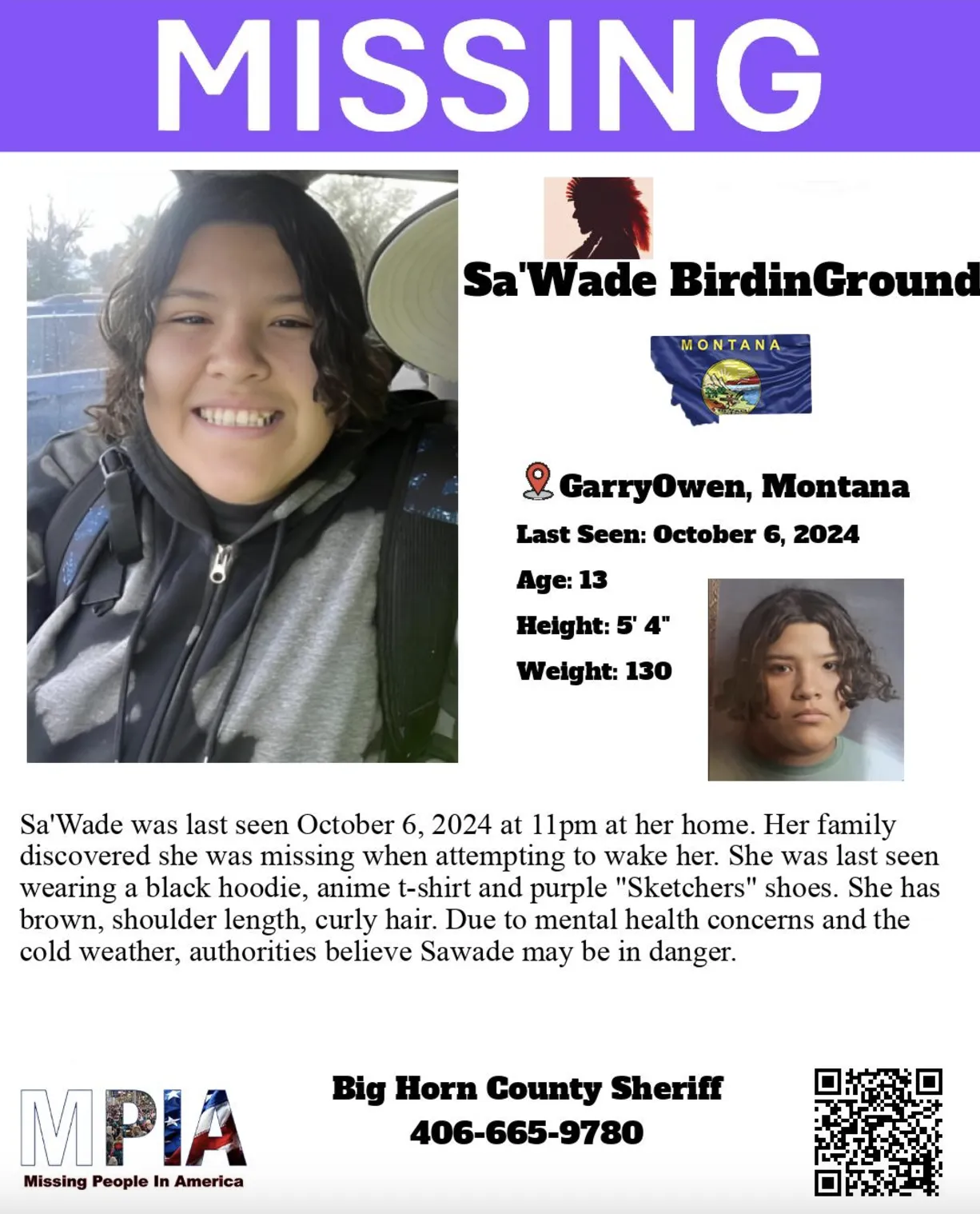

Sa’Wade Birdinground is a typical girl who recently moved from being a pre-teen to a young teenager. The 13-year-old member of the Crow Tribe went missing from the reservation near Garryowen, Montana, on Oct. 6. She was discovered missing from her room when a family member went to wake her up.

“The search continues and there is no additional information that can be released at this time,” FBI spokesperson Sandra Barker told The Daily Muck in a Nov. 21 email.

The family, community, Big Horn County Sheriff’s Office and FBI have mounted an exhaustive but unsuccessful search of the area.

Concern has increased as the temperature in Montana has fallen dangerously low. The reservation’s proximity to I-90 raises the grim prospect that while she voluntarily left her home, she could have been abducted after she left.

“Please check cars. Ask your friends, kids and neighbors,” Wade Birdinground posted in a Facebook appeal. “I’m worried about my daughter. It’s really cold outside. I’ve been searching and it’s getting very cold fast!”

The FBI reported in an Oct. 19 press release there have been “no known contacts with her family or friends since she disappeared.” As of the last report, that is still the case.

The FBI’s Salt Lake City office said Sa’Wade is “a quiet, kind and artistic child who likes to laugh. Sa’Wade is well-liked by her peers and teachers. She has never run away from home or been in any serious trouble. Her disappearance from home is totally out of character for her, and her family is very concerned about her.”

In that press release, Big Horn County Sheriff Jeramie Middlestead called for the community’s assistance.

“We are doing everything we can to bring Sa’Wade home safely,” Middlestead said. “The community’s help is crucial at this time, and we urge anyone with information to come forward immediately. Sa’Wade’s family is deeply worried, and any information, no matter how small, can make a difference.”

FBI Acting Special Agent in Charge Rhys Williams said the FBI is working with local law enforcement and is “asking for the public’s assistance in locating her – and we won’t stop until we have answers. If you have any information, please contact us.”

With Sa’Wade missing for over six weeks at the time of the interview, “we are taking this case very seriously and chasing down every lead,” the FBI said. “Investigators are searching, canvassing multiple neighborhoods, and interviewing members of our community.”

As of the publication date, Sa’Wade has been missing for three months.

Sa’wade Birdinground is 5’4″ to 5’5″ tall, weighs 130-140 lbs., has brown eyes and brown, curly hair. She was last seen wearing a black hoodie with mushrooms on it, an anime T-shirt, basketball shorts and purple slip-on Sketchers-brand shoes. She may also have a black and purple Adidas backpack and is known to wear an elk tooth necklace.

Anyone who sees a young girl matching Sa’Wade’s description or has any information about her disappearance should call the Big Horn Sheriff’s Office at 406-665-9798, the Salt Lake City FBI at 801-579-1400, the nearest FBI field office or their local law enforcement agency, or by submitting a tip online at tips.fbi.gov

Disturbing Statistics of a National Tragedy

The Department of Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs discusses the sobering statistics in a report on the topic of missing/murdered Indigenous people.

It states approximately 1,500 American Indian and Alaska Native missing persons “have been entered into the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) throughout the U.S., and approximately 2,700 cases of murder and non-negligent homicide offenses have been reported to the Federal Government’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program. In total, BIA estimates there are approximately 4,200 missing and murdered cases that have gone unsolved.”

The BIA, to its credit, does not try to hide the reasons for this inactivity.

“These investigations remain unsolved often due to a lack of investigative resources available to identify new information from witness testimony, re-examine new or retained material evidence, as well as reviewing fresh activities of suspects.”

The report also does not shy away from the particularly disturbing evidence that “Native American and Alaska Native rates of murder, rape, and violent crime are all higher than the national averages. When looking at missing and murdered cases, data shows that Native American and Alaska Native women make up a significant portion of missing and murdered individuals.”

The BIA says non-Hispanic Indigenous females “experienced the second highest rate of homicide in 2020. Additionally, in 2020, homicide was in the top 10 leading causes of death for AI/AN (American Indian/Alaska Native) females aged 1-45. More than 2 in 5 non-Hispanic AI/AN women (43.7%) were raped in their lifetime.”

This demographic class was also the second-highest homicide rate for males and was in the top 10 causes of death for indigenous men ages 1 to 54.

Some may conclude that the crisis of murdered, missing and violence against Indigenous people is a product of the reservation. This is another case of victim-blaming and is not borne out by the evidence.

The Columbia Mailman School of Public Health noted in a March 2023 article that “between 86-96 percent of the sexual abuse of Native women is committed by non-Indigenous perpetrators who are rarely brought to justice.”

The ‘Wind River’ Effect

The Wind River Reservation is the seventh largest in the United States. It has a reputation of being one of the most dangerous places in the country due to a high crime rate and other factors.

A Life Daily report notes the reservation has a crime rate about seven times greater than the national average. Even a law enforcement “surge” to address crime -– successful on other reservations -– had no effect. Crime actually increased by seven percent during the operation.

For the purposes of illustration only, we look at the MMIP numbers for Wyoming, where Native Americans comprise about 2-3 percent of the population. Wyoming is sparsely populated and has fewer murders and missing people each year than most mid-size cities. However, the statistics support national reports about the disproportional percentage of Indigenous people among America’s missing and murdered citizens.

In its 2023 update on missing and murdered Indigenous people, the Wyoming Survey and Analysis Center (WYSAC) noted that Wyoming is home to 13,000 Native Americans, with 61 percent of those living in Fremont County, on or near Wind River Reservation.

“Despite representing a small portion of Wyoming’s population, Indigenous people experience violence more often than other racial groups,” WYSAC states.

The update referenced the January 2021 report, which found that between 2000 and 2020, “Indigenous people were 21% of all victims of homicide in Wyoming and had a higher homicide rate than White people. Only 30% of Indigenous victims of homicide received newspaper coverage compared to 51% of White victims of homicide. The limited media coverage was more likely to contain violent language, portray the victim negatively, and provide less information than articles about White homicide victims.”

The organization looked at missing persons cases from 2011 to September 2020, finding there were 710 Indigenous people reported missing. Of those, 57 percent were female, and 85 percent were under 18.

“In 2022, White people made up 76% of Wyoming’s homicide victims,” the report continues. “While correct, this basic calculation conceals a significant and ongoing disparity. For example, although less than 3% of Wyoming’s population is Indigenous, Indigenous people accounted for 12% of all homicides in 2022.”

Comparing homicide rates

Rather than just looking at one-year totals, WYSAC developed a homicide rate – occurrence per 100,000 population – over a five-year period to compare the murder rate between Indigenous and white Wyomans.

“In 2022, the Indigenous homicide rate was 18.3 per 100,000,” the report says. “The homicide rate for White people was 3.2 per 100,000, and the statewide rate was 3.8 per 100,000. The Indigenous homicide rate was more than five and a half times higher than the White homicide rate.”

Murder is more common among men than women, regardless of ethnicity. WYSAC found the 2022 homicide rate for Indigenous women was 10 per 100,000 and 2.3 per 100,000 for White women. The rate was 26.4 per 100,000 for Indigenous men, compared to 4.2 per 100,000 White males.

In the two years between WYSAC’s reports, the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) opened cases for 216 missing indigenous individuals. Most were from Fremont County.

“In 2021 and 2022, the majority of missing Indigenous people were female,” WYSAC states. “Most were between the ages of 5 and 17 when they were reported missing.”

At the time the 2023 report was released, there were 97 missing people in Wyoming, with 11 being indigenous individuals.

“Of the 11 Indigenous people with open records in NCIC, as of December 31, 2022, the shortest amount of time an actively missing person was missing was 13 days. The person missing the longest was reported missing in July 2019 and has been missing for 1,271 days.”

Speaking With Sitting Bear

Sitting Bear took a brief break from fighting a particularly nasty wildfire season to speak to The Daily Muck about this important and often invisible national crisis.

“This is a crisis that affects all tribes in the country,” Sitting Bear said. “It is not only a public safety crisis, but a health crisis as well. It is not just about the women and men, girls and boys, that go missing. It is not just the ramifications and the trauma endured by the victims. It has a cascading effect. It affects the families of these victims, even long after the case is resolved.”

There should be no difference in the response of law enforcement, the media and victim/family support agencies to a report of a missing Caucasian woman, a Native American woman or a victim of another ethnicity, she said. Unfortunately, that is not always the case -– especially for women living on remote reservations.

“You can see this difference in attitude in the coverage by the media, the rapid response by law enforcement to investigate, the implementation of proactive programs in the community, and the support for the families of victims,” Sitting Bear said. “I am not saying that the case of a Caucasian mother of two is not deserving of the attention it receives. It is very important. What I am saying is that all of these cases deserve attention, regardless of race or tribal identity.

“The response should be the same every single time,” she continued. “None of us are safe until all of us are safe.”

Many Causes for Missing People

Sitting Bear said there are many causes for why people go missing. One particularly alarming reason is the increase in human trafficking in this country and worldwide.

“Other reasons can be related to drug or alcohol abuse, mental health issues, or as simple as having a serious accident,” she added.

A recurring problem in the case of missing Indigenous people is a tendency to blame the victims, applying long-held but debunked stereotypes of “life on the reservation.”

“You hear, ‘Oh, he probably just got drunk and wandered off. He’ll be back soon,’” Sitting Bear said. “Or, ‘I’m sure she just ran away. She’ll come home.’ People tend to judge these people by these beliefs and feel that whatever happened to them is their fault. The fact is that these people need to be found.”

She said the problem is exacerbated by the reservation’s status as a sovereign nation and the remote location of many of them.

“It is easier for them to be victimized because they are accessible to those who wish them harm, and it is easier for those people to get away with their crime,” Sitting Bear said.

‘Missing White Woman Syndrome’

WYSAC’s 2023 update says its research found that “the coverage of missing White women tends to be more extensive and sensationalized than that of missing women of color. This leads to a distorted public perception of crime and a lack of attention and resources for finding missing people from marginalized communities.

“When the media gives more coverage to missing person cases involving attractive, young, White women than missing people of other demographics, it is called Missing White Woman Syndrome,” the WYSAC report continued, pointing out “several examples of young White women and girls who went missing and whose cases received extensive media coverage and, therefore, widespread public interest, stand out.”

This attitude in the media “reinforces stereotypes of White women as innocent and needing protection, while women of color are often portrayed as promiscuous or criminal,” WYSAC contends. “Harmful stereotypes can influence how law enforcement investigates and prioritizes cases, leading to a lack of attention and resources devoted to finding missing people from marginalized communities.”

WYSAC echoes Sitting Bear’s comments, saying, “It is critical to recognize that every missing person case is equally important, regardless of the race, gender, or socioeconomic status of the individual. The media plays a vital role in shaping public perception and must be held accountable for equitable reporting. This is essential, especially for missing persons, because public attention could aid in finding the person.”

A Damning Indictment of the Media

In its initial report on this crisis, released in January 2021, WYASAC noted that “media portrayal of missing persons differed between Indigenous people and White people. White people were more likely to have an article written while they were still missing (76% of articles on White missing people, compared to 42% of articles on Indigenous missing people). Indigenous people were more likely to have an article written about them being missing only after they were found dead (57% of articles about Indigenous missing people, compared to zero articles about White missing people).”

The organization said 23 percent of articles about missing White people “said they were found alive and well, while zero articles discussed missing Indigenous people who were found alive and well.” Another major difference in media coverage was that only 12 percent of articles about an Indigenous missing person “contained a photo of the missing person, whereas 33% of the articles about White missing persons contained their photo.

“Negative character framing (emphasizing negative aspects of the victim’s life, family, and community that are unrelated to the crime itself) was found in 16% of the articles about Indigenous people. None of the articles about missing White people included negative character framing,” the report stated.

“Positive character framing (emphasizing positive aspects of the victim’s life, family, and community that are unrelated to the crime itself) was present in 43% of the articles about White people, compared to 38% of the articles about Indigenous people.”

History of Lies and Broken Treaties

Sitting Bear is encouraged by the attention and the promises of assistance and resources to address this social crisis – but guardedly so.

“I am proud to be an active partner with the federal government in my position at the EOC,” she said, “but -– and I don’t want to offend anyone -– the U.S. government has broken every treaty they ever signed with Native American tribes. That’s just a fact. The history of the U.S. government is not a positive one with the tribes.”

The major improvement at this time is the government’s inclusion of Native Americans in the decision-making process.

“For too long, we were not given a seat at the table,” she said. “Decisions affecting us were made without our input and often without our knowledge. We want to make sure we are heard. The Advisory Council was a good start, but it should have started sooner.”

No Longer Sitting, Waiting; Now Standing, Taking Action

In the past, Native American tribes spent most of their time “sitting and waiting for the federal government to do something,” Sitting Bear said. “Now a lot of people are standing up and taking action to solve this and other problems. Many are pushing for positive change, but they need to but they need to keep pushing.”

The MHA Reservation has recently established a Search & Rescue Team, with a tracking bloodhound, to aid in finding missing people.

“We have found one teenager who was missing,” Sitting Bear said. “We make this service available to everyone, regardless of whether they are tribal or non-tribal.”

A Federal Call to Action

Officials with the Department of Justice and Department of the Interior met in September with tribal leaders, media representatives and other federal officials to discuss the overall issue of missing and murdered Indigenous people, and especially how the media can aid in combating this crisis.

In a report on this meeting, the DOJ said there were seven field hearings and a virtual national hearing in which those affected by the issues of missing/murdered Indigenous people and human trafficking “shared their concerns about lack of media coverage and whether that may contribute to cases being ignored or going unsolved.”

Attorney General Merrick B. Garland said media and social media attention “can be crucial in finding and investigating cases of missing or murdered Indigenous persons.”

Garland said the hope is that the government initiative will strengthen the partnership of law enforcement, victims’ families, advocates, and journalists in responding “when a member of a Native community is reported missing.” He said those partnerships “are essential to advancing our shared goal of ending this crisis.”

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said the Biden administration is “committed to fulfilling our promises to Indian Country.” Haaland authored the Not Invisible Act while she was in Congress.

She said the September roundtable was “part of that promise as we act on one of the Not Invisible Act Commission’s recommendations because a crisis that exists in silence will never be solved.”

Garland said the Justice Department will award over $210 million to Indigenous American communities “to support a wide range of public safety challenges. These funds will go directly to efforts to support tribal safety. They include programs dedicated to reducing domestic violence and sexual violence, supporting victims of crime and providing resources to law enforcement, tribal youth programs and treatment programs.”

Principal Deputy Associate Attorney General Benjamin C. Mizer said immediate alerts from media and social media are “a powerful tool to get the word out fast when emergencies happen” and can “help resolve missing persons cases.”

Interior Department Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland said the “overarching principle that guides our work is to make life better for people in tribal communities and making sure that Indian people have the opportunity to live safe, healthy, and fulfilling lives in their tribal communities.

“Public safety is a big part of this,” Newland continued, “and addressing the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples crisis and human trafficking are at the forefront of our public safety work.”

Advisory Council Recommendations

The THSAC that Sitting Bear co-chaired issued several recommendations in its final report.

A major finding of that committee was the “limited communication and information sharing, the need for further education and awareness training, and data compilation and centralization as primary obstacles that require further attention to make a significant impact on the crisis of MMIP.”

The committee said there is no centralized data collection point, “which diminishes the quality, timeliness, and success in tracking missing and murdered Indigenous persons cases. There is no efficient information-sharing process between state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) law enforcement and public safety.

“Tribes do not have equitable access to resources, information, and services,” the report continues. “Geographical and environmental factors contribute greatly to the number of missing and murdered Indigenous people.

To address these identified shortfalls, the committee made the following recommendations:

- Create a designated and centralized standalone Tribal Nation Platform for data collection and networking, one that is secure, current, near real-time, and in line with today’s technological standards.

- Establish a component of the standalone Tribal Nation Platform that provides data analysis.

- Establish uniform criteria for reporting requirements and a process of mandating reporting requirements for missing persons.

- Provide additional training to law enforcement and other stakeholders to support adopting new and existing information-capturing Systems.

- Implement a Whole Community Approach strategy to strengthen the prevention and mitigation of MMIP. Standup an awareness campaign to connect law enforcement, SLTT officials, non-governmental organizations, and all community stakeholders working in the MMIP realm to promote proactive and consistent coordination and collaboration.

The Advisory Council concluded its report by noting, “It is essential that there is buy-in among Tribal Nations to support a DHS-initiated Tribal Nation Networking Platform. If we are to recommend and ask for DHS to partner with Tribal Nations by building a platform under its umbrella, we must have Nations prepared to join and participate in such an endeavor.”

The council said creating an appointed tribal membership among the participating nations would “help to assuage any concerns among Nations and dispel any notion that this is only a federally driven initiative.”

As with anything else, the key to success is adequate funding. The council said this initiative “will require funding, staffing and maintenance, in addition to the buy-in from Tribal Nations.”

‘Gone With the Wind River’

So it appears the key elements of a solution are in place. The need for action is clearly demonstrated in statistics and the voices of those most affected. Authorities in position to fund, implement and carry out programs to prevent such incidents and resolve this epidemic of death and loss have pledged their commitment to the effort. Recommendations on what to do and why it needs to be done have been studied, researched and presented.

All that remains is for the promises to be fulfilled. In a world where the “hot” issue of the day remains popular only until another one comes along and moves it to the back burner, this is the part that may be the hardest of this years-long effort.

In the opening credits of the classic 1939 film about the “Old South,” Gone With The Wind, the filmmaker gives the viewer an insight into the name of the movie and the novel on which it is based: “Look for it only in books, for it is no more than a dream remembered. A civilization gone with the wind.”

Will the same words appear on a screen 75 years from now about how there was once a civilization that ended due to violence and indifference to their pleas for help? Will that film be entitled Gone With The Wind River?

For more in-depth articles, features and news analyses on important issues, subscribe to The Daily Muck.

Discover More Muck

Online Bodybuilding Coach Exploited Minors, Collected Explicit Photos

Report Strahinja Nikolić | Feb 26, 2025

Faces of the Missing: Many Native Americans Remain ‘Lost’; Murders Are Unsolved Mysteries

Feature Raymond L. Daye | Jan 21, 2025

Cult Senior Members Convicted of Human Trafficking

Report Strahinja Nikolić | Oct 10, 2024

Weekly Muck

Join the mission and subscribe to our newsletter. In exchange, we promise to fight for justice.

Weekly

Muck

Join the mission and subscribe to our newsletter. In exchange, we promise to fight for justice.