Why Doesn’t Facebook Do Better Against Scammers?

Why is Facebook so prone to scams? And why aren’t they doing a better job of stopping them? Could they intentionally be allowing scams to remain on their platform?

Let’s take an in-depth look at these questions and try to figure out why Facebook doesn’t do a better job blocking scammers.

The Connection Between Fraud and Social Media

History recorded its first fraud all the way back in 300 B.C. when Greek corn-shipping partners Hegestratos and Sdenothemis took out insurance against their cargo so they could enrich themselves from a “planned accident.”

Fraud and scams probably existed even before that– for as long as humans have interacted with other humans in order to exchange goods and services. Where you find people and the possibility for profit, scams and fraud are sure to follow.

These days, a fair amount of scams are initiated online, where people spend increasing amounts of time. Within the virtual realm, we spend an average of 2.5 hours on social media per day, according to GWI, a consumer research firm.

In fact, one in four people who have been scammed out of money since 2021 said the scam started on social media, according to a report by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). That’s roughly 65,000 of the 257,945 reported cases in the U.S. alone– frauds and scams that started on social media.

The Prevalence of Fraud on Facebook

Finding scams on Facebook isn’t difficult. Fraudsters act boldly, going after people who they consider “low-hanging fruit”– people they think might be susceptible to their scams.

Studies indicate that Facebook has the highest rate of scams among social media sites. F-Secure, an internet security company, conducted a study in 2022 that found 62% of Facebook users encounter a scam at least once per week. F-Secure is an internet security company. Its social media study involved 1,000 U.S. residents.

And Facebook isn’t alone in the social media Hall of Shame when it comes to scams. TikTok and WhatsApp came in second and third place at 60% and 57%, respectively, in terms of the percentage of users that encounter scams at least once a week, according to the F-Secure study. Facebook’s parent company, Meta, owns WhatsApp. Another Meta company, Instagram, had a scam-per-week percentage of 56%.

The “safest” major platform with the lowest likelihood of users encountering scams on a weekly basis was LinkedIn, also according to F-Secure. But LinkedIn still had a robust slice of users (31%) who said that they saw at least one scam per week on the platform.

Personal Experience with Facebook Fraud

One of my many brushes with Facebook scams happened one day when my news feed showed an ad for one of my favorite t-shirt brands. They were advertising their products for a lucrative 80% discount.

The site represented itself as Grunt Style, which sells American and military-themed clothing and accessories. The link above will direct you to the legitimate business. The screenshots are from the fake impersonator on Facebook.

But as you can see from the screenshots, the ad looked legit. I had no reason to question the ad, which– as you’ve probably guessed– turned out to be a scam. Whoever had placed the ad had stolen video content of the actual company announcing a sale.

Hurriedly, I clicked on it, looking forward to grabbing a bunch of my favorite t-shirts for three bucks apiece.

The click led me to a website that, at first blush, seemed like the real thing. But as I added things to my cart, I began to notice anomalies. For one thing, the website didn’t have the company’s official URL, though it was close. For another, there were some misspelled words and unattractive font that seemed off-brand.

Navigating to the Facebook page that was running the ad, I saw the page manager’s location was China, which seemed at odds with the supposed U.S. veteran-owned business.

Fortunately, it wasn’t too late. I hadn’t purchased anything or entered my credit card number. But I had been tricked into going to a malicious site by a scam ad on Facebook, where anything could have happened.

Fake Accounts on Facebook

Many scam attempts on Facebook originate from accounts that are fraudulent in one way or another. Sometimes, scammers steal access to legitimate credentials, locking a user out and taking over their account to run scams on their friends and followers.

Other times, scammers create new accounts of people or businesses, as in my experience with the fake t-shirt company.

How many fake accounts are there on Facebook? It’s impossible to know for sure, but the number of routine monthly users is telling. Facebook had 2.9 billion monthly active users as of the end of 2023, according to its own data.

If that data is correct, 36% of the world’s 8.1 billion population are active Facebook users. That includes people in countries where Facebook is banned– like China– which represents 1.4 billion of that 8.1 billion world population total.

It would also mean that well over half of the internet users in the world– nearly 5.44 billion in 2024, according to Statista– are unique Facebook users.

Anecdotally, these figures suggest a high portion of accounts might be fraudulent since more than a third of all the men, women, and children on Earth are probably not active Facebook users. Some of those accounts are bound to be run by scammers.

Not that Facebook is lying about these user numbers. As far as it– or anyone else– knows or can prove, these accounts represent the true identities of legitimate Facebook users.

Given all these restrictions, it’s a stretch to think that four out of ten people in the world are active Facebook users.

Reporting Fake Accounts on Facebook

When you come across what you believe to be a fake or compromised account, including one that is impersonating another person or business, Facebook recommends that you report it.

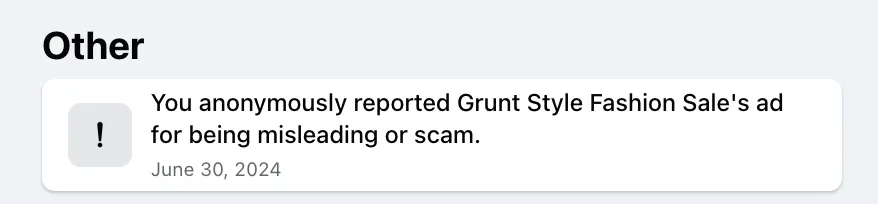

In my case, with the t-shirt brand. I did just that. I reported both the ad and the brand for violating Community Standards, which is Facebook-speak for what the company does and does not allow on its site.

After clicking submit, a notification popped up assuring me that Facebook’s content moderation team would look into the ad. I was confident that the fake company’s days on Facebook were numbered. Feeling good about what I’d done, I was convinced Facebook would take the ad down, preventing other users from falling victim to the company’s misrepresentations.

Except it didn’t happen that way.

Allowing Scams to Persist

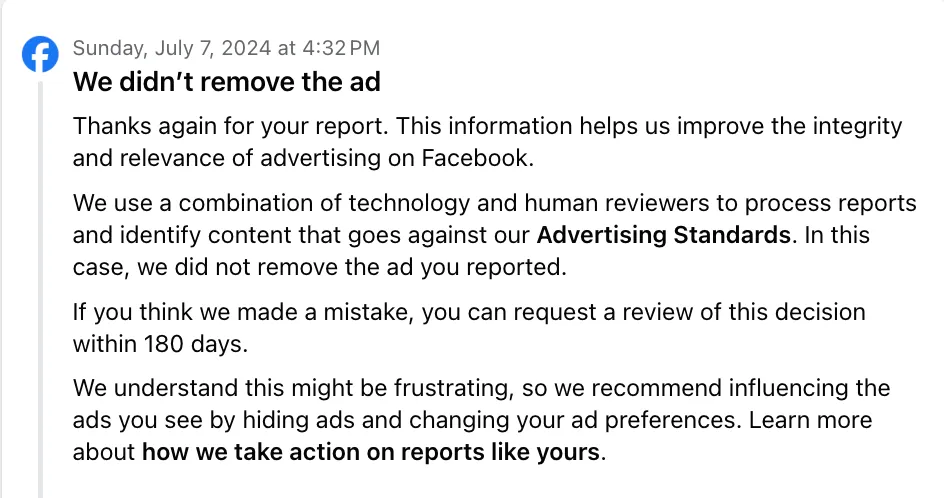

Two days later, I received another notification from the content moderation team. This one said the investigation found the fake community hadn’t violated Facebook’s Community Standards, which, by the way, do include a prohibition on “fraud and deception.” Impersonating another company constituted, according to its own definition, one of the unacceptable business practices, according to Facebook.

This floored me because Facebook’s investigation should have clearly determined the ad was fake, especially since the real company in question has a large Facebook presence, both in terms of its ads and its social media posts.

But the notification gave me an avenue to appeal their decision, and they would look into the matter further. Feeling uneasy about the situation, I clicked the appeal option, still believing that a higher-level reviewer from Facebook would figure out the right thing to do and do it.

Scams on Facebook

Why would people impersonate others on Facebook? Sometimes, it could be as innocent as setting up a fan page in the name of a celebrity, though this type of page should be marked accordingly.

Usually, though, people hack, steal and create fake pages with one purpose in mind: scamming their fellow human beings for all the money they can get.

Facebook Marketplace scams are another way people try to scam you on Facebook. In this case, people often use hacked accounts to avoid being banned from the site.

I’ve Landed on the Scam Site… Now What?

Let’s say you click a fraudulent ad and end up on a scam site. What happens next?

It depends on the type of scam they are running. They might entice you to place an order that you never receive in an effort to steal your credit card number. In that case, fraudulent charges might start popping up on your account almost immediately.

They might just want to sell you cheap, substandard stuff. This is still fraud because you won’t be getting what you think you’re getting.

And the third possibility is they might not send you anything at all, though they have charged your card. In this case, they don’t steal your card number for other fraudulent charges, but you are still out the cost of the item.

In my case, I have no idea what the scam site would have done if I had made the purchase, though I suspect they would have sent me a counterfeit item after charging my card.

Types of Scams on Facebook

Scammers target people on Facebook through a plethora of scam techniques, including the following:

- Account hijacks

- Impersonations

- Fraudulent products and services

- Malvertising

- Cloaking

- Phishing

- AI misrepresentations

- Pyramid and Ponzi schemes

- Investment schemes

- Marketplace scams

- Spam messages

- Free money/ lottery scams

You can read about these scams and how to protect yourself on our Facebook Resource page.

Scams abound on Facebook in terms of both number and variety. But why?

Let’s examine two possible answers to this question.

Case 1: Facebook is Doing All It Can to Stop Scams

The first possibility is that Facebook is doing all it can to stop scams, though its efforts have been ineffective at ending fraudulent practices.

If we accept this case, then the problem is simply too big for Facebook to solve.

To evaluate whether Facebook is doing all it can to stop scams, let’s take a closer look at these efforts.

A Coherent Policy Against Scams

First, Facebook has published and routinely updates its Community Standards, which prohibit scams and other forms of fraud and deception.

The policies are coherent and leave nothing to the imagination. As new scams emerge, Facebook updates these pages, as their change logs indicate.

It is clear from these policies that Facebook bans all manner of fraudulent behavior on its pages, a great first step in providing its users with scam-free experiences.

Reporting Mechanisms

In addition to its prohibition of scammy content, Facebook also enables any user to report any content at any time, including profiles, posts, messages, ads and even hashtags, according to its Reporting Center.

Filing reports is easy… a couple of clicks is all it takes. For ease of use, it’s a ten out of ten, which likely incentivizes people to report it.

Additionally, reporting is anonymous, so users can feel free to call out bad behavior when they see it– even from friends and acquaintances– without fearing recrimination from the person they are reporting against.

In my case, however, Facebook’s reporting mechanism failed to correctly identify and remove the fake t-shirt vendor. Approximately two days after appealing their original decision, I received a second notification that once again found the fraudulent and did not violate their Community Standards, even though the company running the ad was impersonating another company.

There was no option to review the decision a third time. Customer service at Facebook basically doesn’t exist. At one time, it was possible to contact Facebook customer support through phone or email. Now, customers have to fill out forms and are restricted to picklist responses in most cases. Whether reports are ever looked at by a human is debatable.

A week later, I once again checked the report I made against the scam ad. Facebook still hadn’t reversed its decision, and the same scam company was still up and running ads.

The only difference was it had changed its name and was now impersonating a totally different company.

Insisting on Authenticity… Ostensibly

Aside from its Community Guidelines banning fraud and reporting mechanisms, Facebook has a third point in its favor as evidence of its sincerity to stop fraud. Facebook insists its users be authentic, registering for their user profiles using their true identities.

Facebook wants you to have one– and only one– legitimate main profile in your own real name, at least according to its profile help article. Under your main profile, you can have up to four additional profiles, but you are not supposed to create multiple user profiles. Even business pages are supposed to be linked to an authentic Facebook user.

By insisting on authenticity, Facebook attempts to take away one mechanism scammers often use to hide their identities… the impersonation of others.

AI Detection

Facebook monitors adherence to its Community Guidelines, in part, using AI.

“AI can detect and remove content that goes against our Community Standards before anyone reports it,” boasts Facebook in an article about how it moderates content.

By that reckoning, AI can suss out fraud and scams on Facebook without any human help at all.

Facebook does acknowledge that humans can be a helpful part of this process, however. “Sometimes, a piece of content requires further review and our AI sends it to a human review team to take a closer look,” said the article.

Using AI can be an excellent method of discovering fraud. Models use machine learning to identify patterns of scams that might be difficult for humans to detect.

Using AI to spot fraud is further evidence that Facebook is serious about deterring fraud.

Restricting Offenders

Further evidence supporting the case that Facebook is doing all it can against fraud is the fact that it punishes offenders who violate its policies against scamming.

Facebook uses a “strike” system to dole out punishment to scammers and other policy violators. Sanctions range from warnings for first offenses all the way up to 30-day content bans for “ten or more strikes,” according to Meta’s “Counting Strikes” policy.

All strikes expire after a year, according to Facebook policy.

Deleting Fake Accounts

Once Facebook conclusively determines an account is fake, it bans it, more evidence that it is allocating significant resources to detecting and disabling fraud.

In fact, Facebook deletes hundreds of millions of accounts it deems fake every quarter, according to Statista data. In their highest quarter to date, Jan-Mar 2019, they deleted 2.2 billion fake profiles… in only three months– more evidence that Facebook is doing everything in its power to deter fraud.

Case 2: Facebook Intentionally Enables Fraud

Yet even with all of its efforts, scams are still visible to six out of ten users on a weekly basis. This begs the question: is Facebook really doing all it can to stop fraud?

There remains the possibility that Facebook turns a blind eye to or possibly even enables fraud to occur on its platform, especially when it comes to fraudulent ads and other paid posts. Its revenue model may incentivize it to do so.

Facebook Ads = Facebook Profit

In 2023, Meta’s overall ad revenue exceeded $131 billion, according to Meta data compiled by Statista. Its total revenue was $134 billion, meaning the total of all of its non-ad revenue sources put together was only about $3 billion.

Since 98% of Facebook’s revenue comes from ads, serious efforts by Facebook to curb scam ads would slaughter its financial bottom line. This fact exerts friction against Facebook’s motivation to rid the platform of fraud altogether, even if Zuckerberg isn’t secretly meeting with senior execs to plot out how Facebook can seem serious about combatting fraud without actually being serious.

Ditto with non-ad scammers on Facebook. The platform is already deleting tons of fake profiles every quarter. If it were to crack down on the problem comprehensively, how many of Facebook’s 3 billion users would turn out to be fake?

Deleting more users would also hit Facebook’s bottom line. Fewer users equals fewer ad impressions, which equals less ad revenue.

Facebook Continually Falls Short

But even more damning than the fact that Facebook would be cutting into profits by getting serious about scams is the fact that Facebook continually falls short on its efforts.

Facebook is a company that can do anything, from re-inventing social media to changing the landscape of friendship and communication to significantly contributing to artificial intelligence via its big data aggregation.

Facebook has fine-tuned the art of showing me an ad for a purse I complimented a friend on at our lunch an hour ago (though, for its part, Facebook claims not to listen to our conversations.) And yet, it can’t stop a fake ad from luring me to a scam site even when all the indications are there, and I (and assuredly others) report the ad multiple times?

Yes, combatting fraud is difficult. But Facebook is known for doing difficult things.

So Does Facebook Intentionally Collude with Scammers for Profit?

The extent to which Facebook wittingly colludes scammers is unknowable, at least with the evidence The Daily Muck was able to dig up. But Facebook’s commitment to reducing scams is questionable, given the way they continue to proliferate across the platform. We invite you to consider both cases and formulate your own opinion.

By the way, The Daily Muck did reach out to Meta for comment on its fraud detection and prevention methods, but their response– much like their customer service– was nonexistent.

Discover More Muck

First AI-Powered Lawsuit Exposes California’s Eco-Fraud Empire

Feature John Lynn | Apr 10, 2025

Former Child Soldier General Lied to Get Green Card

Report Strahinja Nikolić | Feb 27, 2025

Weekly Muck

Join the mission and subscribe to our newsletter. In exchange, we promise to fight for justice.

Weekly

Muck

Join the mission and subscribe to our newsletter. In exchange, we promise to fight for justice.