A Tale of Two Judges

San Francisco judges Harold Kahn and Rochelle East embroiled in case-rigging scandal involving judicial extortion, $500 million Bitcoin embezzlement scheme, over 5,000 victims

It wasn’t a memorable day. I don’t even remember what the weather was like. My only obligation was to attend a meeting on Zoom for what the California Superior Court calls a “Mandatory Settlement Conference.”

About 5 years prior, I had brought a lawsuit against my former business partner, Patrick Strateman. We co-founded Intersango, which was once the world’s second largest cryptocurrency exchange. Strateman had forced me out, stolen all the company profits and it was looking more and more like he had embezzled our client’s funds.

The settlement conference was officiated by Judge Harold Kahn. It started pleasantly enough. Harold Kahn introduced himself and boasted at having settled hundreds of cases.

Soon enough, the tone would turn.

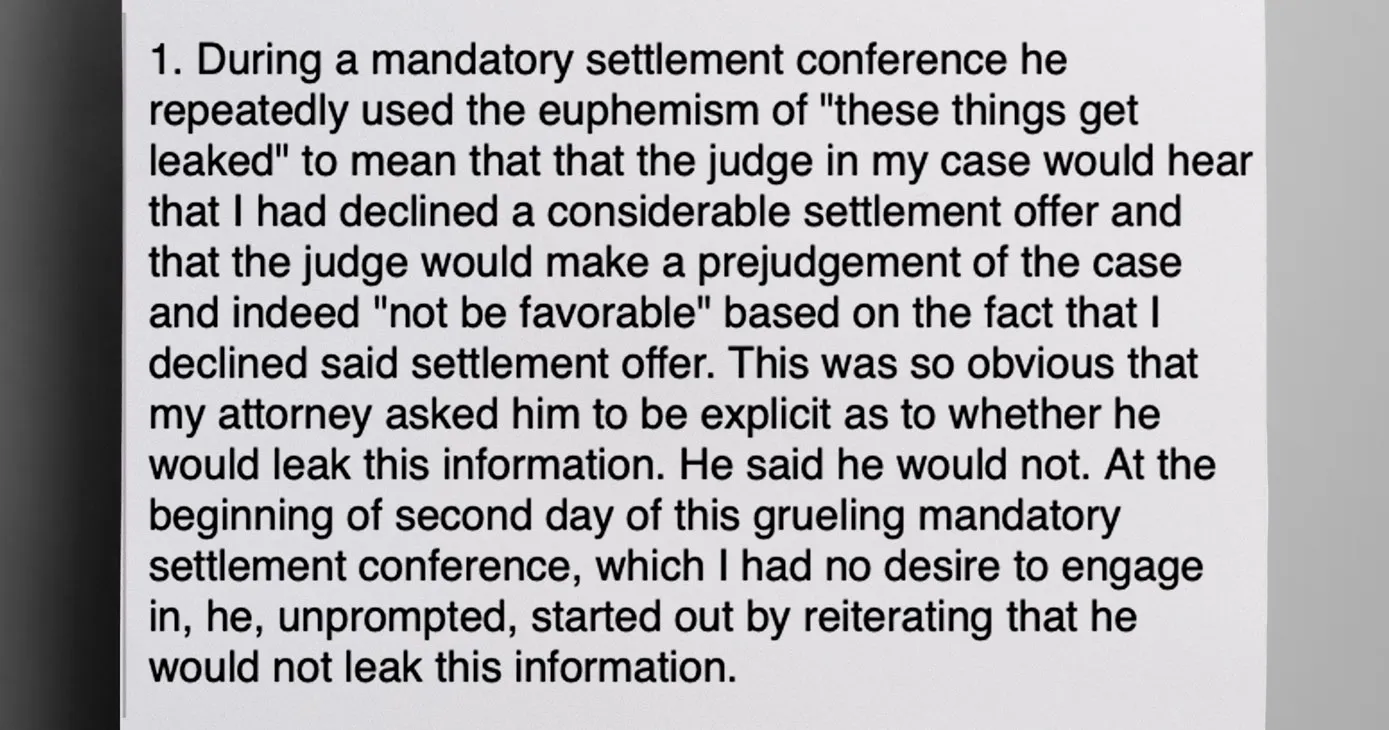

Judge Harold Kahn would go on to repeatedly insist I accept a settlement offer from the defendant, Patrick Strateman. Harold Kahn repeated ad nauseam that he knew how these things went. What happens in the settlement conference “always gets leaked.”

When the trial judge, Judge Rochelle East, finds out that I turned down a multi-million dollar settlement, Judge East would “not be happy” and would come down hard against me.

In essence, Judge Rochelle East wouldn’t decide the case based on the facts. No, she would punitively rig the case against me for daring to waste the court’s time. Harold Khan hoped to ensure a settlement by undermining my faith in the justice system.

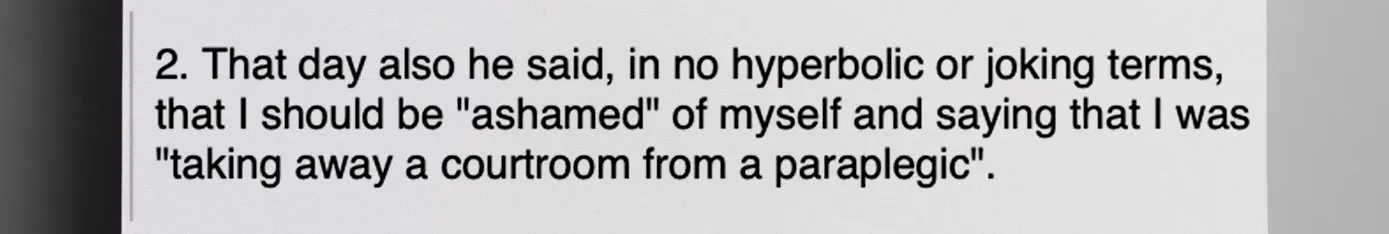

The next day, Judge Kahn would turn to ridiculous shame tactics, saying that I didn’t have the right to a trial and that I should be ashamed of myself for choosing to take a lawsuit to trial. He argued that the courts were clogged and that, if I insisted on a trial, I would be taking away a courtroom from a paraplegic. There were people far more deserving of a trial and I wasn’t one of them.

Eventually, I did take the case to trial and, in doing so, exposed a mass embezzlement scheme where my former business partner stole assets currently estimated at around half a billion dollars. Strateman stole this amount collectively from over 5,000 of our clients.

Had I accepted the settlement offer before taking the case to trial, evidence of the embezzlement would remain confidential and have never entered the public record. Settling the case at that time essentially meant accepting a bribe.

Thankfully, as an early investor in bitcoin, I was under no great financial pressure to take a bribe and walk away. I needed to know if there had been mass embezzlement. To put it bluntly: I could afford to sue. Most of the people Strateman had stolen from could not, and I felt an obligation to represent their interests in court. The company that had ripped them off was one I had co-founded.

Was the lawsuit about money? Of course it was. But it was never just about money.

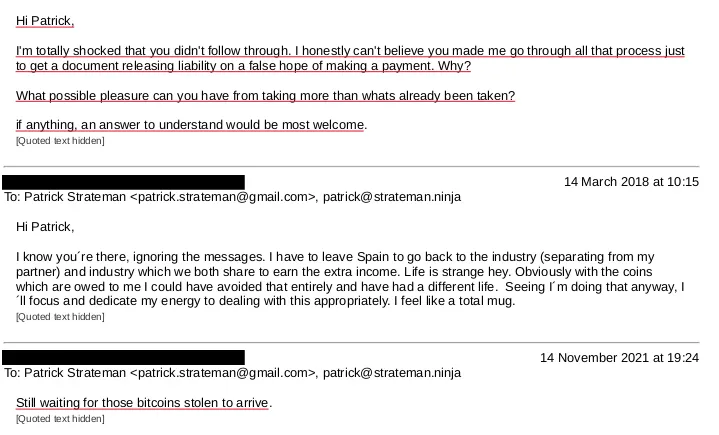

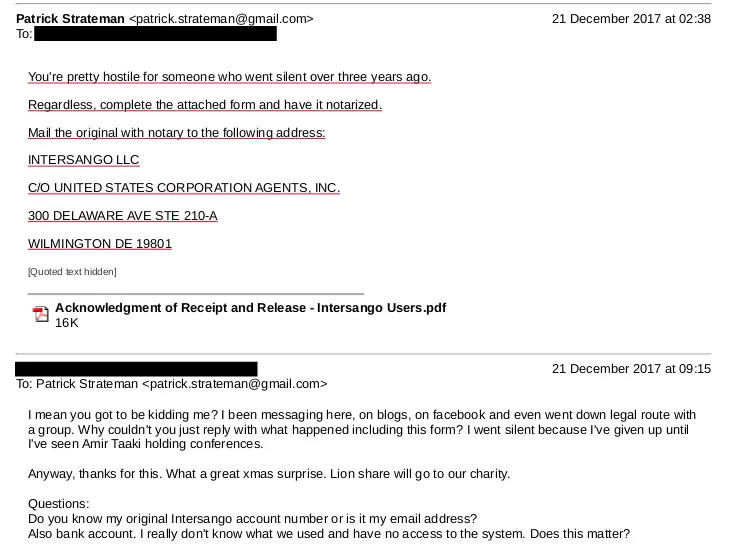

Many victims of the embezzlement would later provide a treasure trove of emails and other corroborating evidence to their claims. The evidence shows Strateman repeatedly preying on the desperation of customers, giving them false hope and keeping them at bay by always saying he would pay up, just at a later date.

Much like the famous Nigerian 419 email scams, there was always one little thing preventing payment, one more obstacle, one more issue that needed resolving or one more hoop the client had to jump through before being made whole.

In one instance, a victim, after years of pleading for his funds, told Strateman he would have to leave his pregnant wife to take a job halfway across the continent unless Strateman paid him what he was owed. Read his full declaration to the court here.

In another instance, a college student not only had his own funds stolen but also his friend’s funds. His declaration to the court states he had to work extra hours for months to repay his friend.

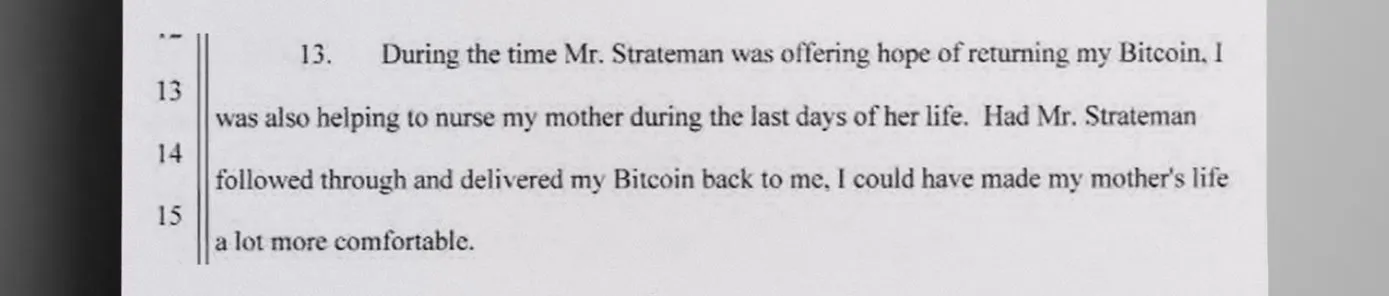

There is a declaration from a single mother and another where a victim talks about how he attempted to collect leading up to his mother’s death. Had Strateman paid this victim what he was owed, while he would not have been able to save his mother, he would have been able to provide her with far more comfort in her final days.

Unfortunately, all of this is just the tip of the iceberg. To this day over 5,000 people are still owed.

Does Judge Kahn’s attempt to strong-arm a settlement constitute extortion? Threatening legal harm to a litigant for exercising their right to a trial would seem to be the very definition of extortion – and it is, in fact, a crime under California law. By doing so Judge Harold Kahn betrayed the course of justice, his oath of office, and may have ultimately helped brush a half-a-billion-dollar embezzlement scam under the rug.

Judicial Corruption in the U.S.

Judicial corruption is not an anomaly. A 2020 Reuters article identified thousands of cases where judicial misconduct occurred between 2008 and 2019. The real number is likely much higher as many instances go unreported due to cumbersome bureaucracy and, in some places, the requirement to make statements against judges under penalty of perjury.

After already suffering court malfeasance, those affected may not think it worth the risk to lodge a complaint, especially when judges who admit to serious misconduct face relatively little in terms of consequences.

The aforementioned article detailed the tragic tale of a woman named Marquita Johnson and a judge “who unlawfully jailed hundreds of poor people, many of them Black, over traffic fines.”

According to the article, “Judge Les Hayes once sentenced a single mother to 496 days behind bars for failing to pay traffic tickets. The sentence was so stiff it exceeded the jail time Alabama allows for negligent homicide.”

While in jail, Johnson’s three children were put into foster care where one was molested and another physically abused.

According to Reuters, “Hayes, a judge since 2000, admitted in court documents to violating 10 different parts of the state’s judicial conduct code. One of the counts was a breach of a judge’s most essential duty: failing to ‘respect and comply with the law.'” Hayes relied on what he called a “gut instinct” to determine guilt. He was suspended for 11 months without pay before returning.

“Hiring Hayes back to the bench was a slap in the face to everyone,” Johnson said in her interview. “It was a message that we don’t matter.”

Why Judges Commit Crimes

Judges find themselves on the wrong side of the law for various reasons. A lack of accountability can cause them to abuse their personal discretion and prioritize it above the law, as in the case of Judge Hayes.

Another reason, however, relates to the demands of expediency. Expediency is often directly at odds with justice. For every piece of evidence a judge can throw out, their workload is that much lighter. Judicial bias tips the scales in favor of quick unexamined decisions, something that can be easily abused by malicious actors.

State, county and municipal courts have to contend with 100 million new cases per year. Dividing this by the 30,000 judges across the 50 states, the average judge has to process more than 3,300 cases per year. That comes out to over 13 cases per workday per judge.

Not surprisingly, litigants often report feeling that judges don’t even read or look at case material before making a decision. The very reason it is common to hear judges open up hearings by commenting that they have read the fillings is specifically because judges often don’t, in fact, read the fillings.

While many cases are quickly processed in traffic court, a judge in civil court tasked with a case that may entail a significant amount of time has all the more reason to discreetly rig that case in the interests of expediency. This can be done by throwing out evidence and, in an even more insidious manner, by finding out which litigant is unwilling to settle and repeatedly signaling that the case will be rigged in the other litigant’s favor – in other words, exactly what Judge Harold Kahn had said would happen.

There is a reason the judge overseeing settlements is different from the one presiding over the trial. There is supposed to be an impenetrable wall of confidentiality between the two judges; they’re not supposed to speak at all about the case. But Harold Kahn said the trial judge — the judge I would face if I didn’t take the deal — would decide against me, not based on the merits of the case, but as punishment for my (to him) unreasonable attitude.

How would the trial judge even know there’d been an offer? How would she know that I was the one who’d refused to settle, and not the defendant? Who would tell her, if not Judge Kahn?

This threat was coupled with Judge Kahn’s insistence that an audit of the company finances was “off the table.” Kahn was adamant. He would not even relay the request for an audit to the other side. It was a case of “take the money or else,” but without an audit, there would be no chance to expose any potential embezzlement at the company.

In essence, accepting a settlement offer would be no different than being party to the embezzlement itself. I had no choice but to press on.

Mandatory Settlement Conferences

Lawsuits are not only costly to the people involved but also to the state. And because there are not enough judges to adjudicate cases, there is great pressure on judges to force settlements.

Who exerts this pressure on judges is outside the scope of this article but an expression of this pressure can be seen when California requires litigants meet to try and hash out their dispute. These Mandatory Settlement Conferences can help those involved, but they can also help the state avoid a costly trial and clear the seemingly impossible backlog of cases in front of the courts.

The Background

In 2017, I brought a lawsuit against a former business partner. Years earlier, we had become co-founders of Intersango which became, for a time, the world’s second largest cryptocurrency exchange.

While the defendant, Patrick Strateman, alleges I abandoned the company in late 2012, his testimony shows my departure was in many ways similar to a forced termination.

On the stand in 2022, Strateman confessed to failing to make payments for months leading up to my departure. Evidence also shows he repeatedly promised and then failed to provide company accounting data. He would never provide this data. It’s the same playbook Strateman would use against the company’s many clients.

While the exchange started from a modest apartment that we shared with the third co-founder Amir Taaki, by September 2012, we had spent over a year operating the business from behind our computer screens, each logging in from a different country.

When I met up with Strateman in person in London in late 2012 for a conference we helped organize, Strateman was supposed to finally pay me money that was owed and that I needed to keep working for the company. When he came empty-handed, was dismissive and acting strange, I knew something was very wrong.

I was at the end of my rope, in a foreign country with few friends and no cash on hand, with a business partner who had been promising for five months to provide company accounting records yet failing to deliver.

I could have sold some bitcoin in person in a manner that would now be considered illegal, but at the time, due to the unregulated nature of cryptocurrencies, would simply be legally dubious. However, doing so would have also been against our agreed-upon operating protocols.

Being the operators of an early crypto-exchange, I felt we needed to be beyond reproach. That ruled out selling in person. And to sell through an exchange would mean it would take days, if not over a week, for funds to arrive.

I knew I needed to take care of myself and that I couldn’t, at least in the interim, rely on Strateman or the company financially (he had full access to company funds for security purposes since he was the CTO). I appealed to the third partner, Taaki, but he was of no help. I also began to see Strateman’s failure to provide accounting data in a new light and started to worry about his potential criminal malfeasance. So, I left.

I returned home and, no longer having a source of income, moved in with my girlfriend’s parents. I had never met her parents but I showed up to their humble abode with all my worldly possessions, a laptop and enough clothes to fill one check-in and one carry-on luggage. What happened? To answer that, we need to go back to when it really started.

Amir Taaki, then one of the lead developers of the open-source software project, had introduced me to Bitcoin over Skype. After a couple hours of reading and asking him a few questions, I understood the groundbreaking nature of cryptocurrency.

To say Bitcoin or cryptocurrency had potential would be an understatement. Would someone say the printing press or the computer simply had potential, or did their early adopters understand these Promethean technologies had already been passed down and were here on earth? They didn’t need to wait to know the world had already changed, they could see it with their own eyes.

Having been a frequent traveler, I knew the limitations of modern international finance that Bitcoin had already solved, even if Bitcoin hadn’t been adopted yet. That afternoon I bought a ticket from Singapore and left the next day to meet Taaki in Amsterdam.

After landing in Amsterdam, I immersed myself and learned everything there was to know about Bitcoin. At one point, while sitting on a couch at one of Taaki’s friend’s apartment, I took out a small piece of paper and did some paper-napkin math. Based solely on a nominal number of markets that I truly understood, markets in which Bitcoin would have a monopolistic advantage, I sought to calculate a fundamental value for the price of a single bitcoin.

My incredibly conservative math came up with a price of $900 per coin. Bitcoin was trading at around $1.15. I pretty much considered myself set for life there and then. What’s more, any market that wasn’t included in my calculations, where Bitcoin would provide a merchant or customer with a monopolistic advantage, could only drive the price up even higher. And there were far more markets out there that I didn’t understand than those that I did.

Eventually, the critical mass necessary for Bitcoin to overtake gold as a store of wealth, because in many ways cryptocurrencies are superior for storing wealth, would be accomplished. I bought as much as I thought prudent and told myself to reevaluate when the price reached $900 a coin.

I worked day and night, at least 80 hours a week, building infrastructure around cryptocurrency like Intersango, or speaking at conferences. I was quoted in the first ever articles on cryptocurrency and Bitcoin for Reuters, Newsweek, WSJ and countless others. I truly believed I was changing the world. To this day, some of the phrases you will hear at conferences around the world to explain and promote cryptocurrency are ones that I devised.

So it should be no surprise I was quoted in the first Newsweek article to mention Bitcoin and cryptocurrency:

“Norman says the power of Bitcoins is that they can free people from the tyranny of middlemen: banks; credit-card companies; and money shippers like Western Union, which charge exorbitant fees for performing a rather simple task.”

or the first two articles to mention cryptocurrency in WSJ:

“Bitcoin is going to change the world in the same way the Internet did and make societies freer.”

But I no longer had an income and it took a long time for our exchange, Intersango, to break even. I subsidized the entire operations of the company for the first eight months from my own meager savings that I had spent years building up. By the start of 2012, I had put all my savings into the company and was only left with those bitcoin I had bought eight months prior.

As I saw my savings dwindle, I eventually drew a line in the sand and told myself I would live under a bridge for a decade if that’s what I had to do before I would sell any of my bitcoin. You couldn’t even buy a nice car with how much I had at the time but it was my retirement plan. It was my future child’s birthright. And I was dead serious. What happened in the end wasn’t so far off.

While I never had any intention of being my generation’s most prolific hodler, it is a title to which I now lay claim and it would be the reason I was able to bring this lawsuit and spend millions not even knowing if I would ever collect or if Strateman had spent what he had stolen from me.

When you sue a large company, it’s in their interest to pay up to keep operating. When you sue an individual, they can hide assets. They can move overseas. There’s a million things they can do to not pay. But when I finally brought my lawsuit, I also wanted to know what happened. Why did Strateman kick me out? Why did he run the company into the ground? Did he embezzle from the clients?

Returning to 2012, the company had begun to break even and by the summer profits were coming in. The cost of operations had significantly lowered due to many automations that were now in place and due to having already laid all the groundwork necessary to run the company. For the first time, the company was sustainable and even making decent money.

Unfortunately, as many clients discovered after Bitcoin’s huge price spike in December 2013, when Patrick Strateman starts seeing dollar signs, bad things happen.

Things Fall Apart

When I met Strateman in person in London for the conference, after he had failed to send bank payments but promised to give me cash in hand, he showed up empty-handed. I had stretched my last pound out to that meeting. I was only able to return to my friend’s apartment that night where I was staying because the tube pass I had was good for the whole day. That night the friend who I was staying with lent me cash and I got the first ticket out.

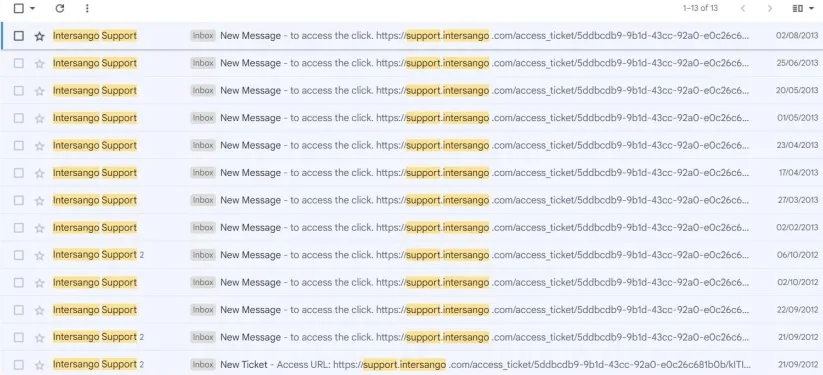

Strateman would claim my physical departure, even though we worked remotely online, meant that I abandoned the company. He would use this as a pretext to begin his embezzlement plan. Within less than a week, his first victim would make a request for his funds.

Just like Strateman accused me of abandoning the company, years later he would similarly accuse a client. Despite years of attempts at collection, Strateman claimed that the client abandoned his claim. The client’s attempts included: numerous emails to Strateman, emails to Taaki, joining a collective legal action against Strateman and participating in an online forum as well as a Facebook group set up to address the ongoing embezzlement.

In other instances, Strateman acted threatened by clients attempting to contact him through his family. The offer of one gentleman to fly from his home in New Zealand to the United States to collect a life-changing sum of money was met defensively, as if the offer was a threat.

According to that victim’s court declaration, had he been paid during the time Strateman was leading him on, he would have been able to provide far more comfort for his dying mother in her final days.

What is known is that mere days after I was cut out, Strateman started preventing clients from accessing their funds. It started with the teacher in the UK but over time there were others.

That all changed when, after a cataclysmic rise in the price of Bitcoin in late 2013, one that to this day stands as the biggest 30-day percentage increase in Bitcoin’s history, Strateman restricted withdrawals from the platform en masse and then took down the website altogether.

Thousands of clients could no longer access the millions of dollars in cryptocurrency they were owed. Today, due to the rise in the value of cryptocurrency, the amount still being embezzled is estimated to be around half a billion dollars or more.

While it is unclear if Strateman squandered much of the client funds he was entrusted to protect, a recent investigation looking at public blockchain data has been able to confirm he still has access to over $200 million worth of client bitcoin.

The Lawsuit

In 2017, after Strateman failed a self-imposed deadline to distribute site profits and provide an accounting, I finally brought a lawsuit. I was seeking my own claims but also, and perhaps more importantly, determined to find out if client funds had been embezzled, something that was still only a strong suspicion.

During the discovery process of this lawsuit, a lot of evidence suggested that mass embezzlement had, in fact, occurred and was still occurring. While many of the emails and corroborating evidence shown in this article should have been provided by the defendant in the course of the lawsuit, they were never provided and only discovered recently.

The evidence that I did have that indicated embezzlement was deemed confidential by the court and there was still no smoking gun. Furthermore, my attorneys were barred from deposing the witness about this evidence. In effect, I ended up in a court-ordered conspiracy. I was sitting on all this evidence but not allowed to disclose it.

By bringing the lawsuit to trial, I would be able to enter this evidence into the public record but doing so was far from an easy task. I would have to endure hours and hours of berating from Judge Harold Kahn that was more akin to psychological torture than a settlement conference, all while donning a smile so as not to further upset the judge. This was compounded by the fact that I didn’t have the right to a jury trial, only a bench trial.

The article titled “Death of The American Trial Lawyer,” written by U.S. district judge Mark Bennett, explores the loss of the jury trial in civil cases and even the loss of the trial altogether.

Bennet writes, “Many judges in both state and federal courts have embraced a philosophy of discouraging trials and view themselves solely as case managers. Many judges see jury trials as a burden or a ‘failure’ of the parties to reach a resolution. Rules, policy statements and judicial expectations in many jurisdictions place emphasis on how quickly they dispose of cases, resulting in some judges pressuring parties to settle and adopting the view that a case going to trial is a failure of the system. They often profess, ‘a compromised settlement is always better than a great trial result.’”

Judge Kahn earned his reputation as an expert settler of cases by honing his skills across his over two decades on the bench. Looking closely at his history, it is easy to see how he is perhaps the best suited judge to pressure litigants to settle cases.

The Settlement Judge – Judge Harold Kahn

Judge Harold Kahn, who it seems never needed a single vote to retain his position on the bench, might best be known for settling cases.

When he first opened up the Mandatory Settlement Conference bragging about having settled over 200 cases, it was a seemingly innocuous statement. But his success at settling cases may simply be a byproduct of his willingness to empty the docket at any cost.

According to the Practicing Law Institute, a nonprofit legal educational institution founded in 1933, Harold Kahn “removed a backlog of over 600 cases, resulting in the first time in almost two decades that the Court was current with its asbestos cases.”

Judge Kahn has given two interviews that can be located. One is a fluff piece about handling pressures of the court and the incessant workload. And the other is aptly titled “Running on empty: SF’s sole law-and-motion judge keeps things moving…” The title betrays that Harold Kahn’s judgeship seems to have revolved around expediency. It’s as if the man’s entire career is devoted to clearing the docket and justice isn’t even an afterthought.

Judge Harold Kahn doesn’t go so far as to openly state judges are the real victims, but he sure comes close. How can a judge possibly be expected to carry the burden of such a workload? The fuller context of expediency and the corrupting pressures on judges make Harold Kahn’s appeals to these overwhelming pressures of the docket read less like a method to convince litigants to settle and more as an instrument of mental gymnastics. Is it all a justification for him to accommodate his own conscience? The judge doth protest too much, methinks.

Last November, Judge Harold Kahn gathered with a group of other judges in protest. It wasn’t about the heavy caseloads or the extreme pressures litigants face to settle their cases. It wasn’t about expanding the number of judges in San Francisco. It was about judicial challengers who had been criticizing San Francisco’s soft-on-crime stance.

“The San Francisco Standard” penned an article memorializing the protest, “San Francisco Lawmaker Denounces Judicial Challengers.”

While Judge Kahn is not directly quoted in that article, a fellow judge and the former presiding justice of a division of the California Court of Appeal, Anthony Kline, was adamant judges in the United States could be bought, just not in San Francisco. Judge Anthony Kline said, ”You know, you can buy a judge in Texas, but you can’t buy a judge in San Francisco.”

From the outside, the group of judges sure seems like an old boy’s club. As if the old guard, now worried about being displaced by what they call political rivals, is calling foul. If the new crop of challenging judges can be bought, as Kline suggests, with judges like Harold Kahn, does it matter?

How much of the desperation seen on the streets of San Francisco is a reflection of the corruption that goes on in the courthouses? When do you lose your mandate? When is it no longer politics?

A Closer Examination of Judge Harold Kahn’s Extortion

One thing I’ve learned is criminals love euphemisms. The defendant, Patrick Strateman, used euphemisms to keep me at bay while he embezzled millions and then Judge Harold Kahn did the same in an effort to force a settlement.

Harold Kahn knew what he was doing was wrong and repeated the phrase “these things get leaked” both to undermine faith in the justice system but also to distance himself from his actions and add a thin veneer of plausible deniability.

Had Judge Kahn stopped at saying it just once, it might be excusable. But when a judge repeats over and over again that the trial won’t be judged based on the facts but instead based on my unwillingness to accept a settlement offer, something doesn’t add up.

As a society we often give undue respect to judges. Being addressed as “Your Honor” day in and day out may have a corrupting influence on some judges.

It was respect for the robe which led to my incredulity. I just didn’t get the hint. I thought I was going to be in the presence of someone who devoted their life to the law and justice but found someone who wouldn’t even pay lip service to justice.

I was so incredulous, I remember asking myself that first night, “Why isn’t Kahn an advocate against court corruption if it’s so bad?” It was me not getting the hint that caused Harold Kahn to repeat his extortionary euphemism ad nauseam.

At some point, Judge Kahn must have realized he overstepped his bounds. The next day, unprovoked and dropping all pretense, he opened up the settlement conference saying that he would not leak information to the trial judge. This time he was speaking in first-person.

Despite walking back his comments, Judge Kahn’s tenor shifted again. He switched to shame tactics. He would go on to berate me for hours in an attempt to coerce a settlement. When you’re essentially stuck in a meeting with someone who spends hours repeatedly shaming you, when you’re explicitly told by a judge you don’t have basic rights such as the right to a trial or that if you should be ashamed of yourself, because, if you bring your case to trial, you will be taking away a courtroom from a paraplegic, it really messes with your head.

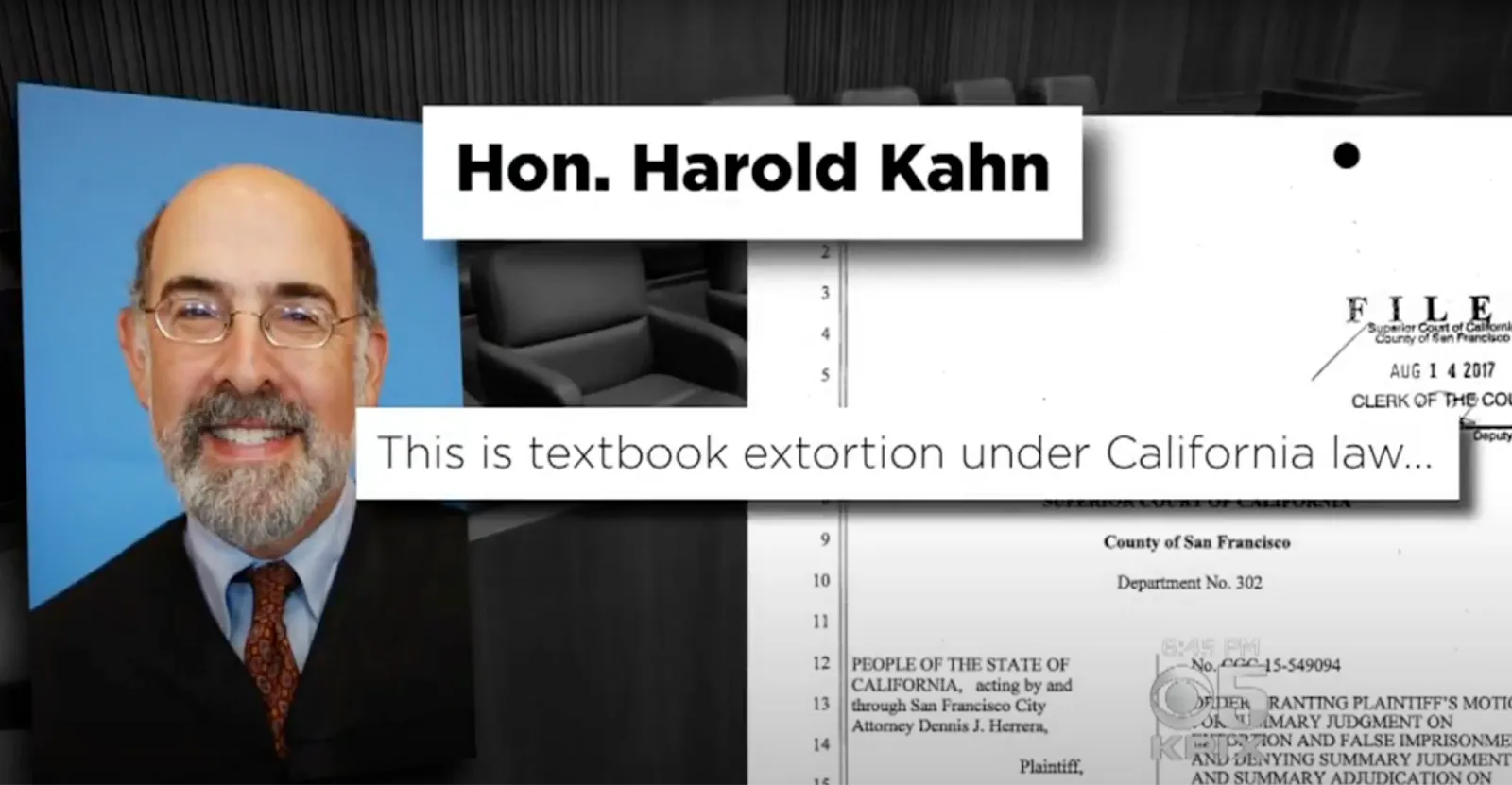

These tactics are eerily similar to what Judge Kahn condemned as “textbook extortion” and “black letter false imprisonment” when he passed judgment over the actions of a company called CEC.

San Francisco City attorney Dennis Herrera, who brought the suit against CEC, said they failed to accurately depict the fact that prosecution was in no way a given.

However, there seems to be no mention or even suggestion that CEC undermined faith in the justice system to coerce suspects into taking a deal, as Judge Kahn did.

Why Lawyers Don’t Stand Up to Corruption

In theory, attorneys in California have the right to file what is known as a 170.6. California law, on the books at least, suggests that litigants need not prove a judge is prejudiced to request a recusal, simply that a reasonable person would agree the litigant has reason to doubt the impartiality of the judge.

I was never made aware of this standard and the entire trial was dominated by daily reevaluations of whether the trial judge was, in fact, corrupt. And every day the corrupt-o-meter seemed to tick slightly more to the right but you wouldn’t have heard this from any lawyer. Attorneys may have reason to serve the interests of the court above their own client’s interest and even above the interests of justice.

In practice, filing a motion such as a 170.6 may be career suicide for a practicing lawyer, especially one claiming extortionary practices. Lawyers often see the same judges regularly, and falling outside the good graces of the court might pose an existential threat to an attorney’s ability to successfully practice law in that jurisdiction.

If Judge Kahn could sink my case for failing to play ball, maybe he could sink an entire lawyer’s career.

Judge Rochelle East

When Kahn’s repeated bouts of legalistic arm-twisting (and the defense’s ever increasing bribes) proved ineffective on me, he was forced to let my case proceed to trial. This would be presided over by the Judge he insisted he would never leak to – though he was equally adamant that, somehow, word of my uncooperative spirit would leak to her, and that she would decide against me because of it. This judge’s name was Rochelle East.

Much like Kahn, Judge Rochelle East seems to have never received a single vote. After being appointed by Governor Jerry Brown in 2013, Ballotpedia shows that in 2014 Judge East “ran for re-election to the San Francisco County Superior Court. As an unopposed incumbent, she was automatically re-elected without appearing on the ballot.”

Similarly, in 2020 Ballotpedia notes that Rochelle East “won re-election for judge of the Superior Court of San Francisco County in California outright in the primary on March 3, 2020, after the primary and general election were canceled.”

According to a fluff piece from “The Daily Journal,” Rochelle East spent much of her life in the system. Growing up in a globe-trotting family, in places like Japan, suggests she may come from a diplomatic or military background.

Raised in a diplomatic household myself, I’ve seen my fair share of parents stewarding their children into cushy, albeit often mundane, government jobs. If being a lifelong bureaucrat teaches people anything, it’s how to game the system.

Whether or not that was the case for Judge East, after getting a bachelor’s degree and then graduating law school, she confined herself to a government salary for the next three-and-a-half decades.

Still, her career has been illustrious. According to a press release from the San Francisco California court website, Judge Rochelle East’s jobs ranged from serving “as an officer in the U.S, Navy for 10 years, including two tours as the war briefer for two 4-star commanders-in-chief during Operation Desert Storm in the 1990-1991 Gulf War.” The press release also reports that Judge East served as a Foreign Service Officer with the U.S. Department of State.

The most interesting part of Judge Rochelle East’s resume, however, regards her appointment by then Attorney General Kamala Harris as chief deputy of the California Department of Justice. According to the release, “As the chief deputy, she was responsible for managing more than 5,000 employees, including approximately 1,000 attorneys and a $1 billion budget.”

Illustrious as Rochelle East’s career may be, while outwardly serving the public, the hierarchical and bureaucratic nature of her positions have always been to follow orders and to give orders. I’ll get to why that’s important later.

The Trial

Before I recount my trial experience, please let me apologize in advance if my description ever seems extreme, or histrionic, even… unhinged. I really am trying to put the facts in front of you as objectively as possible but, frankly, the American legal system beat a lot of the reasonableness out of me. Until you’ve experienced a trial at its worst, you can’t understand how maddening it is.

In a follow up to this article, I will delve deeply into irregularities which plagued the trial. The two most notable incidents were:

- Judge Harold Kahn exiting from the same judge’s door as Judge East – Kahn addressed the courtroom off-the-record saying that he and East had spoken and that he would be available for settlement talks.

- Judge Rochelle East pausing the trial twice – Both times suggesting, off-the-record, that the parties settle, once literally threatening “settle or else you won’t be happy.”

Other questionable actions ranged from Judge East throwing out half of my evidence on spurious grounds and referencing details conjured up out of thin air, perhaps relayed by Judge Kahn.

The trial was furthermore marred by unequal treatment.

East stoically listened as the defendant’s case fell apart. Patrick Strateman’s own testimony confirmed mass embezzlement. He admitted to depositing proceeds of client funds into his personal bank account. He was caught lying about why he took down the website, saying he did so in response to a bank closure, when documents proved the bank freeze occurred after and in response to Strateman taking down the website.

Absurdly, Strateman argued cryptocurrency payments to clients were not made due to a lack of banking. Of course, no bank account is needed to make cryptocurrency transfers.

Finally, Strateman admitted failing to provide accounting data or payments months before I was said to have ‘abandoned’ the company.

Despite East’s stoic demeanor during Strateman’s testimony, as soon as I took the stand, East immediately started rolling her eyes and making other off-the-record expressions to signal her displeasure, hence influencing my testimony.

East made it perfectly clear that calling the defendant a thief or speaking ill of the defendant with charged words was unadvisable. But East’s reactions had nothing to do with court decorum as I was not extended the same courtesy.

East allowed the defense to run amuck with Orwellian shame tactics similar to those employed by Kahn, for instance the defense attempted to shame me for:

- Failing to travel to a foreign country to meet Patrick Strateman at a time when Strateman wouldn’t even take my phone calls.

- Failure to disclose company funds to Strateman over a year after he started his mass embezzlement scheme.

- Stopping the defendant from paying people back – Suggesting that the lawsuit I brought two and a half years after Strateman started his mass embezzlement somehow retroactively prevented him from paying people. East surely knows there is no law requiring defendants in lawsuits embezzle their client’s money.

These nonsensical accusations were tactics of psychological coercion. East allowed these shame tactics and more to go on without comment.

In a world where justice is a game and a trial is not about proving a case but forcing a settlement or capitulation, an unspoken – or maybe spoken – collusion occurs between a dishonest lawyer and a dishonest judge. The defense argued that two plus two must equal five, and East was a willing accomplice. If the process was honest, it would have sent the wrong signal.

Despite not commenting on the defendant’s case falling apart, during an off-the-record sidebar, East stated she didn’t trust me and that my story didn’t add up. Even if she believed this, it’s a bit hard to have your story add up perfectly when the deck is rigged.

While the defendant was allowed to speak freely, here are some of the things I had to contend with before every sentence:

- I had to filter out years of evidence and communication, as if they had never happened.

- I couldn’t talk about what I had discovered in the database, which allowed the defense to make statements they knew could be disproved by the database.

- When it came to hush money, East barred us from calling a spade a spade. A $1.5 million payment Strateman made to Taaki two weeks after taking the site down could not be called hush-money or a payoff. After failing to disclose the payment, Strateman recanted testimony to call this payment a “gift”.

- I was surreptitiously discouraged from calling the defendant things like a thief and made to bite my tongue and speak of Strateman in only the most bland of ways, lest not provoke another rolling of the eyes.

- I had to meter my words. The court reporter told me I needed to speak slower or my testimony would not be preserved on the record. She could not keep up with my rate of speech. So, for my entire testimony, I had to unnaturally and awkwardly meter every sentence, which is hardly conducive to a free-flowing stream of consciousness. Not only had I never spoken like that before, I had never had to think like that before.

- I had to be mindful of the defense’s statute of limitations argument. The loss of years worth of evidence leading up to the lawsuit, from the years that directly preceded my lawsuit, meant the defendant’s statute of limitations argument carried far more weight. If I volunteered my suspicions that the defendant’s criminal activity went so far back as to when I was forced out of the company, that would, ironically, only serve to help the defendant’s case.

While some of East’s actions can be put down to expediency, others make it clear she knew which party to lean on.

The trial saw me grasping at straws like the subject of a Milgram experiment trying to justify a trial, that at the back of my mind, I must have known was off. But unlike the famous Milgram experiment, instead of rather simple arithmetic equations, this experiment put me in an unfamiliar world with strange rules and processes.

Fast forward to today, shortly after the last hearing, I finally watched the Christopher Nolan masterpiece “Oppenheimer.” When Oppenheimer is at his lowest, in the middle of a rigged legal process similar to my trial, he’s asked, “Robert, you can’t win this thing. It’s a kangaroo court with a predetermined outcome. Why put yourself through more of it?” Oppenheimer responded, “I have my reasons.”

Not being a resident of California, I was alone in the courtroom, my family thousands of miles away. I didn’t have anyone to explain to me what was and wasn’t normal. My own lawyers had been afraid to file a 170.6 and now they failed to stand up at an obviously corrupt trial. I know it’s ridiculous and I’m embarrassed to say it but I thought, “Why couldn’t I have someone tell me I was in the middle of a kangaroo court?”

I’ll never truly know but I think that after my attorneys failed to file a 170.6 against Kahn, settling the case, in their minds, would help them brush their own liability under the rug. This would also explain why, even months later, they would only begrudgingly admit in the email above to Kahn’s extortionary actions. While the term extortion is not used, the actions described are, in Kahn’s words, “textbook extortion.”

Sympathy for Rochelle East

Rochelle East is soft-spoken, in a way, sympathetic. Between the trial and the most recent post-trial motion, I found myself coming up with justification after justification for Rochelle East’s actions. As a young child of 8 or 9, I remember being told never to accuse anyone without proof. My mother used the old maxim “Better a hundred guilty people go free than one innocent be found guilty.” At that age, you don’t think critically, and this was an unexamined, inherited belief that I carried with me into adulthood. It’s one I still try to live by to this day.

Until a few years ago, I believed this was a shared maxim, something every person knew and every decent person attempted to live by. It’s the reason I didn’t accuse Patrick Strateman of mass embezzling customer funds even after he had embezzled mine. It’s the reason I didn’t get the hint when confronted with Harold Kahn’s repeated euphemisms. And it’s why I wasn’t willing to condemn East simply because of threats Kahn had made.

In attempting to rationalize Rochelle East’s actions, at one point, I even came up with the theory that East is an “eclectic thinker” and not a “dialectic thinker” due to her successes in academia and rigidly hierarchical government structures.

An eclectic thinker would better succeed in academia by not questioning a professor or textbook’s orthodoxy. An eclectic thinker would better succeed in the military by not questioning orders, even being able to hold more cognitively dissonant beliefs than most people. And an eclectic thinker would be wildly persuadable, giving weight to any argument they hear in proportion to its repetition and the emotional charge with which it’s delivered. Methods of persuasion such as the “big lie” and psychological anchoring would find an easy home.

An eclectic thinker might also be able to sit through two weeks of trial and still be under the impression, like East was, that Bitcoin was a company or that Strateman would need a bank account to send bitcoin to the many people he owed.

Like so many of Patrick Strateman’s victims who were gaslit and led on for years, still desperately hoping Strateman would pay up, a big part of me didn’t want to believe that East was corrupt or, as Kahn so much as said, so punitively malicious that she would tank a case because I was wasting the court’s time.

I think a belief in the presumption of innocence will cause people to view you as weak or an easy target. And, eventually, they cross the line in the most unassailable of ways. When, in the latest hearing, East didn’t even pay lip service to a single victim declaration and when she allowed the sadistic treatment of the victim who had to leave his pregnant wife to get a job in a far away country to be called an “honest mistake,” she crossed that line.

The Settlement

By the time evidence of the embezzlement had entered the public record, including admissions from Strateman himself, and after bearing witness to the irregularities of the trial, settling seemed like the only option. The stress from trying to figure out what was going on caused me to lose more sleep than I thought humanly possible. And so I agreed to a settlement.

I thought, with all the evidence now uncovered, that I could finally get some measure of justice for Patrick’s victims. As it turned out, I was right – but also, in the truest possible sense, completely wrong.

I should’ve known my efforts were doomed when I was told that, once again, my old nemesis Harold Kahn would preside over the settlement hearing. Naturally, I requested a new settlement judge. Who wouldn’t? My attorney, however, told me Kahn could not be replaced. I now know this was a lie.

During the continued negotiations, Kahn would relay what he said was an offer from the defense. The defendant would request the ability to keep customer funds, or some portion thereof, and in exchange offer more remuneration. The fact that a judge would be willing to negotiate an embezzlement scheme served as just another in a long line of items to remind me that this was a place devoid of honor and justice.

In the end, I thought I settled the case in a way that accomplished my main goal, to make sure clients were paid back. Patrick Strateman offered me $6 million on top of that as well. At the time, I was still under the belief he had the assets to pay clients back and then some.

It was a long cry from what I had hoped. Before coming to San Francisco, I hoped the court would have seen the light of day, referred the case for criminal prosecution and that the defendant would have been arrested before the case concluded. While that didn’t happen, exposing the embezzlement and negotiating for clients to get their funds seemed like something I could live with. It was more than the FBI and the DOJ had ever attempted to do.

But, something I didn’t understand at the time, a settlement is a contract with another person, it isn’t a ruling from the court. It isn’t backed by the power of the government in the same way. And Judge Harold Kahn, Judge Rochelle East and all the attorneys (including my own) seemed to have little regard for the enforceability of the contract, merely wanting to get out the door.

The Aftermath

Before the ink had even dried, less than 60 days later, a legal filing by Patrick Strateman in another lawsuit sought to deny a client’s claim.

In this other lawsuit, Strateman’s filing argued legal technicalities such as statute of limitations, the argument that he was not a fiduciary, and, contrary to his own trial testimony two months earlier, the declaration that he did not materially benefit from the claimant – Strateman had testified to having sold forked coins, the cryptocurrency equivalent of a stock spin-off and deposited the proceeds into his bank account.

Over the following months, as information of the trial came out, Strateman would continue to ignore client demands for repayment and fight any attempts at transparency.

Furthermore, public blockchain data showed that Strateman was continuing to spend client funds. In fact, newly uncovered information during this time showed Strateman had misappropriated slightly over half of the assets.

It is at this point that Rochelle East was given a further opportunity to ensure these victims were reunited with their property. A motion to set aside the settlement agreement, which the defendant had clearly entered into in bad faith, would have cleared a path to put the company into a receivership and allow an audit. A court-appointed third party would transparently manage the dispersions and return funds to clients who had already waited years.

Since new public blockchain evidence shows Strateman doesn’t have the funds to pay clients back, doing this meant that, very likely, nothing would be left over for my claim. But I don’t want a single penny, let alone $6 million if it would come out of client funds. And blockchain evidence highly suggested that the defendant was attempting to pay me with client money. Unwittingly, I had ended up where I was twice before, being asked to take a bribe.

In the recent hearing to this motion, Rochelle East denied embezzlement was occurring based on a similar type of ‘gut feeling’ that Les Hayes had employed and ignored the mountains of declarations which included smoking-gun corroborating evidence that should have been provided by Strateman prior to trial.

This evidence proved beyond any reasonable doubt Strateman’s embezzlement scheme. Still, East denied the embezzlement, referencing the defendant’s disproven testimony and saying, “That was not my impression at trial.”

When the corruption that occurred during the Mandatory Settlement Conference was brought up, East twice turned a blind eye, choosing to not admit into the record or even hear evidence of the corruption.

It was also during this hearing that Rochelle East agreed with the defense that the aforementioned victim was somehow “an honest mistake.” This is a man who had fought to collect for years with numerous emails to both the defendant and his associate, who joined legal action and participated in collection efforts through a forum and also a Facebook group. This is a man who was given many promises by Strateman across many years only to have Strateman repeatedly disappear.

How anyone can pretend that isn’t embezzlement but somehow “an honest mistake” is beyond me. East also heartlessly failed to even reference a single other claimant or contend with their incontrovertible corroborating evidence.

The motion was drafted with the idea that even the most corrupt of San Francisco judges would not have been able to ignore the damning evidence. I remember telling my friends and family that East “can believe the lies from the defense. She can think I’m an asshole. She can think whatever she wants but she can’t deny the embezzlement.”

I imagined her telling her lobbyist friend, “I’ll keep doing right by you, but this one you have to let go.” Any denial of the embezzlement would be prima facie absurd, but in the end, that’s exactly what happened.

Not only did she completely ignore the evidence but, despite presiding over a trial that lasted two weeks and centered around a Bitcoin exchange and bitcoin owed to thousands of clients, East bizarrely referred to Bitcoin as a company.

East is on the record saying, “As far as protecting the customers and, again, there were a number of companies here, there was Bitcoin, there was Britcoin, there was Intersango, there were a whole lot of companies with different sometimes related names.”

I ask, which is more insane, that after two weeks of presiding over a “Bitcoin” trial East somehow believes Bitcoin is a company or that she intentionally seeks to enter into the record something so absurd as to appear negligent and not malicious?

What’s clear is that this is not a slip of the tongue. Imagine a judge saying the following sentence: “As far as protecting the customers and, again, there were a number of companies here, there was the dollar, there was Google, there was Tesla…” It’s not a slip of the tongue.

We’re left to choose between two equally ludicrous conspiracy theories, a deliberate display of ignorance for reasons of plausible deniability, or truly magnanimous proportions of ignorance. This is the state of the San Francisco court system.

It is hard to place actions which are in line with the desire for expediency down to improprieties or leaks from Judge Harold Khan. Throwing out evidence, the repeated insisting on a settlement, the tacit acceptance of shame tactics employed by the defense and finally the willful denial of embezzlement by the defendant could be an independent result of East’s desire for expediency.

But many actions do betray that East knew exactly which litigant to lean on. And while the nature of the communication between East and Kahn may never be known, there is also the possibility that Kahn misled East for his own ends. One thing said by East at the last hearing was ominous.

In addressing my new attorney, East said, “It may well be that looking back, there were things that if you had been the negotiator you may have — perhaps both sides would have done things, added extra terms or rephrased things, I don’t know. An audit and so forth, sounds like a great idea, it was not part of this settlement.”

It is hard to believe that, had East known Kahn had explicitly denied the ability to negotiate an audit, she would have made such a statement. I think, when it comes to Kahn, there is no honor among judges and he never relayed the full picture to East. In that aspect he also betrayed his colleague.

Right now the decision by East is being appealed.

Unfortunately, my biggest worry for the appeal has nothing to do with the evidence in the motion but the geographic proximity of those making the decision. While the new judges deciding the matter will not be sharing the same hallways with East, the matter will be decided at an appeals court which sits in the building next door. I can only hope that the same threat Kahn made does not extend beyond East. I can only hope that there are some honest judges in San Francisco.

I Invite Judge Harold Kahn and Judge Rochelle East to Sue Me

It was my intention to publish a police report with this article, to go on the record about an incident that happened in front of three attorneys in a way that, if false, could be easily proven and land me in jail. However, the San Francisco Police Department refused to take my report. They don’t file reports for such crimes.

I’ve only come forward after speaking with my family and preparing for the worst. In a country where the average citizen commits three felonies a day and a court system that is capable of punitive prejudicial findings simply for bringing a case to trial, as Judge Kahn made perfectly clear, the old adage “show me the person and I’ll show you the crime” rings as true now as ever. While I fear a manufactured criminal case or being held somehow in contempt of court, no such charges will obfuscate the judicial extortion that occurred and the resulting case fixing which I believe occurred.

In any case, I implore Kahn and East to sue me for defamation. Although rare, a case in Florida already exists where a judge has sued a litigant.

As long as I have the right to a fair trial and a jury, I relish the chance to defend my statements. Can they defend their actions? I will jump through hoops to help establish proper jurisdiction.

Judge Harold Kahn – Where is He Now?

Harold Kahn has since retired. In fact, this was his last case on the docket. One extra consideration or benefit received from the settlement was the ability to start the vacation he had planned with his wife two weeks earlier than he would have had the trial run to its conclusion.

Did Kahn receive anything else? Does it matter? He committed extortion, used coercive shame tactics, and undermined faith in the justice system for his own benefit.

Judge Harold Kahn, your judicial immunity may protect you from formally being held to any account. But I’ve written this article so you might be judged in one court that I do still have a right to, for now at least, the court of public opinion.

Discover More Muck

Neo-Nazis Allegedly Targeted Children for Sexploitation and Self-Harm

Report Strahinja Nikolić | Feb 28, 2025

Feds: South Carolina Duo Harassed and Sextorted Family of Intellectually Disabled Man

Report Strahinja Nikolić | Jan 21, 2025

Weekly Muck

Join the mission and subscribe to our newsletter. In exchange, we promise to fight for justice.

Weekly

Muck

Join the mission and subscribe to our newsletter. In exchange, we promise to fight for justice.