Birthing Expert Says Induced Labor Is Overused

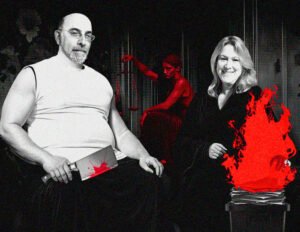

Dr. Rachel Reed (right), a retired midwife and international author, warns that labor induction is increasingly routine—even when there’s no medical need. She says today’s maternity systems prioritize efficiency over physiology, leaving many women uninformed about the risks.

In nations that rely on private or government-assisted health insurance, there is suspicion that money may be the root of this particular “evil.” Inductions and C-sections are more expensive than spontaneous births without complications or interventions.

In countries with universal, low-cost, tax-funded health care, profit may not be the motive, but other systemic pressures can hike the induction rates.

I spoke with a global maternity care expert for her personal and professional insights into this growing trend.

A View from ‘Down Under’

Dr. Rachel Reed lives in Queensland, Australia. Born and raised in northern England, she moved to Australia in 2005. Reed holds a PhD and enjoyed a long career in midwifery and academia before retiring in 2023.

She is an author, educator, researcher and international speaker. Among her many books is Why Induction Matters.

“Inductions for medical reasons can be life-saving for mother and baby,” Reed said. “However, the definition of ‘medical reasons’ has expanded to include variations of pregnancy where the mother and baby are not experiencing any complications.”

Reed said the rise in labor inductions isn’t being driven by expectant mothers. In most cases, healthcare providers bring up the possibility of a “scheduled birth.”

“According to research, most women still aim to have a spontaneous labor and vaginal birth without interventions,” she said. “Few manage this in the current maternity system.”

Reed said medical providers are changing the rules mid-game to comply with laws requiring a medical reason for an induced labor. They have expanded the list of “medical reasons” to create an illusion of necessity.

“There has been a significant increase in ‘medical’ inductions for variations to pregnancy that are not in themselves complications,” Reed noted. “For example, changes to the diagnosis of gestational diabetes have resulted in over 19 percent of Australian women being diagnosed and induced.

“This hasn’t improved outcomes,” Reed continued. “Women are also being induced for big babies, small babies, maternal age, IVF, BMI (obesity) and many other reasons.

“It’s becoming unusual for a woman to get through her pregnancy without being recommended to induce her labor,” Reed observed.

Informed Consent: What Women Aren’t Being Told

Reed said only the woman should decide if she wants an induction without an obvious medical reason. A valid consent requires “adequate information about the risks of induction for her and the baby,” she added.

In the U.S., hospitals and obstetricians may recommend an early labor induction at 39 weeks. While this is generally considered full-term, it’s still two to three weeks before the natural due date.

Reed believes most doctors and hospitals aren’t set up to support the natural birth cycle. Their focus is to respond when something goes wrong, administer pain relief during labor and care for the baby and mother after delivery.

“Hospital systems are very good at managing interventions, including induction,” she said. “Staff are experienced in delivering this care and are more in control of the woman’s body and birth if they are managing the labor.”

As a general rule, Reed said, most women are “poorly informed about the reasons they are being given an induction or the risks of induction in their situation.”

The Medical System’s Mistrust of Women’s Bodies

Medical professionals often have what Reed calls a “general mistrust of women’s bodies. This mistrust has become a self-fulfilling prophecy,” she continued.

The cycle goes like this: First, doctors can’t predict how a woman’s body will respond during labor, so induction removes that uncertainty. The doctor’s initial mistrust can drive unnecessary interventions – inductions, C-sections or the use of instruments — to manage complications that arise during delivery. Ironically, those interventions can create complications, such as excessive bleeding, fetal heart distress or newborn respiratory issues.

This complication confirms the doctor’s initial mistrust of spontaneous labor, Reed said, “and so the cycle begins again.”

“Obstetricians also cherry-pick research that fits their preferences,” Reed continued. A prime example is their use of the 2018 ARRIVE Trial. This study, reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in August 2018, is widely credited with ushering in the so-called “induction age.”

ARRIVE – an acronym for A Randomized Trial of Induction Versus Expectant Management – challenged the long-held belief that induction increases the likelihood of a C-section. The study of 6100 patients found fewer C-sections in the induced group (18.6 percent) than in those who carried to term (22.3 percent).

Reed says doctors often reference ARRIVE without acknowledging other research that shows the opposite. This is especially true for first-time mothers, who often face higher C-section risks after a failed induction.

“Women are also not told about the short- or long-term risks of induction, Reed added, “or how different induction is to spontaneous labor.”

One of the biggest criticisms of ARRIVE is that only 27% of the 25,000 eligible women participated. Skeptics argue that outcomes for the other 73% could have significantly altered the conclusions.

Mistrust can be a two-way street.

“Women who are induced after being told their baby is at risk– often incorrectly– can feel relieved that their baby was saved,” Reed said. “They can also blame themselves and their body. However, when women find out that they were coerced– often when pregnant with their next baby and exploring options– they can feel betrayed and mistrustful of health professionals.”

Efficiency, Not Money

Money isn’t the driving force in countries like Australia, the UK and 22 other nations with government-funded universal healthcare. In those systems, induction doesn’t generate profit, but it may serve another purpose: efficiency.

“I don’t think this is primarily driven by finances,” Reed said. “It is driven by large maternity systems that have historically been set up to run effectively and efficiently, controlling the ‘chaotic’ bodily process of birth.”

“Induction,” she explained, “makes birth more manageable. It’s much more efficient in terms of getting a woman through the system in a timely manner and making use of available resources.”

By contrast, spontaneous labor is unpredictable. Women may be in early labor hours longer than a hospital’s budgeting model allows. The birth suite “may only be funded for 24 hours per woman,” Reed noted. If the labor isn’t progressing fast enough, staff may intervene to speed it up.

Reed also pointed out the financial disparity in systems where profit is a factor. “Obstetric care is more expensive in general,” she said. “In for-profit systems, interventions are more profitable. Therefore, an OB could claim a bigger fee for an induction or surgery than for a physiological birth without intervention.”

Meanwhile, midwives– whose care is more aligned with natural birth – are paid much less than OBs, regardless of the level of intervention required.

The Question About C-Sections

One of the most dreaded– yet increasingly common– interventions is a C-section. This surgical procedure gets its name from a Roman law believed to date back to the reign of Julius Caesar. Caesar decreed that babies be cut out of the wombs of women who died in childbirth. The word “caesar” comes from a Latin verb meaning “to cut.”

For decades, many women avoided induction out of fear it would increase their risk of a C-section. A Cesarean birth not only raises medical costs and extends recovery time, but also robs the new mother of precious time with her baby.

As noted earlier, the ARRIVE findings pushed that bogeyman into the closet. The study gave doctors a new line: Not only will inducing labor not increase the risk of C-section, it actually reduces the risk!

Reed said some obstetricians may be too quick to recommend a C-section, but she doesn’t believe it’s always out of convenience. “I don’t think you can generalize,” she said.

In her experience, fear of litigation plays a major role. “I have been told a number of times by OBs that ‘You get sued for what you don’t do; not for what you do,’” she said.

Reed said this reflects a deeper problem: “The fact that women seldom sue for misinformation, coercion and unnecessary surgeries – because they often don’t know their legal rights.”

Few Women Ask for Induction – So Why Is It Rising?

Reed said she “rarely cared for a woman choosing an induction without a medical reason.” Most of her patients understood that the baby typically initiates labor when ready.

Inducing labor early interferes with what she describes as a “complex physiological process” by triggering labor before the baby or the mother’s body is fully prepared.

Many of Reed’s patients “had a previous induction experience where they were coerced and misinformed about the need for induction,” she said. “These women can be traumatized and want something different for their next birth.”

Reed said induction “entirely alters the birth process,” and women need to be prepared for that reality. “Induced labors are more painful and increase the chance of an instrumental delivery or C-section,” she said, especially for first-time mothers..

“For the baby, the medication used to induce contractions is the leading cause of fetal distress, so the baby’s well-being needs to be carefully monitored,” Reed warned. “The baby is also more likely to be born requiring respiratory support if induced before term.”

Reed emphasized that labor and delivery are orchestrated by hormones that help the baby transition to breathing, support breastfeeding and activate instinctive bonding behaviors. “Induction disrupts this physiology,” she said.

Australian Study Contradicts ARRIVE Findings

While the ARRIVE study found a lower C-section rate among induced patients, an Australian study led by Dr. Hannah Dahlen reported mixed – and in some cases troubling – results.

That study revealed that 45 percent of first-time Australian mothers had induced labor in 2018. The overall induction rate that year was 34 percent.

Despite approximately a third more inductions, the researchers found no significant reduction in stillbirths or neonatal deaths over the past decade – a key justification for early induction.

The study looked at 474,652 births. About 15 percent underwent induced labor for non-medical reasons.

Among first-time mothers, the C-section rate was significantly higher in the induced group: 29.3 percent compared to 13.8 percent in women who went into labor naturally.

The risks don’t stop at delivery. Post-birth hemorrhage occurred in 2.4 percent of the induced group, compared to 1.5 percent of those who had spontaneous labors.

For women who had previously given birth, the data showed a slightly lower rate of C-sections – 5.3 percent versus 6.2 percent – but the overall pattern raised concerns.

“Following induction,” the researchers wrote, “incidences of neonatal birth trauma, resuscitation and respiratory disorders were higher, as were admissions to hospital for infections (ear, nose, throat, respiratory and sepsis) up to 16 years.”

Know All the Facts

“Trust” is a small word with a big impact. If your doctor recommends an induction during a healthy pregnancy, make sure you have all the facts before signing on the dotted line.

Yes, you should trust your medical professional – but you should also trust your body.

Bringing a child into this world hasn’t changed much since Eve gave birth to Cain. The female body has produced many billions of sons and daughters over the millennia.

Perhaps the most important part of the body in your pregnancy is your mouth. In short: ask questions. Ask about anything you don’t understand or anything that makes you uneasy.

Subscribe to The Daily Muck for more in-depth articles and features on this and many other important topics.

Discover More Muck

Dead on ARRIVAL: Fatal flaws in the ARRIVE Trial and Hidden Dangers of Elective Inductions

Feature John Lynn | Sep 15, 2025

Prioritizing Rural Births: Senator Casey Murdock on Enhancing Maternal Care

Report John Lynn | Aug 28, 2025

Advancing Access: Senator Becky Massey on Maternal Health Reforms

Report John Lynn | Aug 18, 2025

Weekly Muck

Join the mission and subscribe to our newsletter. In exchange, we promise to fight for justice.

Weekly

Muck

Join the mission and subscribe to our newsletter. In exchange, we promise to fight for justice.